Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No54

Newsletter Themes: Scotland’s proposed conversion therapy legislation, the undermining of history education and SUE's Annual Conference

The first article in this week’s newsletter, by Alex Cameron, looks at the importance of ‘conversion therapy’ legislation that the Scottish government has committed itself to bringing into force. Like many recent Scottish government laws, there is little demand for this legislation, but rather, it appears to be driven by the political class who think making laws that are distinctly different from Westminster policy is what being in government is all about. Alex explains how the conversion therapy legislation would undermine parents’ rights and must be opposed.

In a SUE review, Rachael Hobbs usefully examines the meaning of history teaching today and summarises how the European Council is degrading history teaching by adopting an approach that projects current political concerns and issues onto everything in the past. In the process of doing this, the history that our children are taught is simplified and becomes little more than an instruction in guilt and shame, where almost all the gains of the past that helped create a free, democratic society are lost.

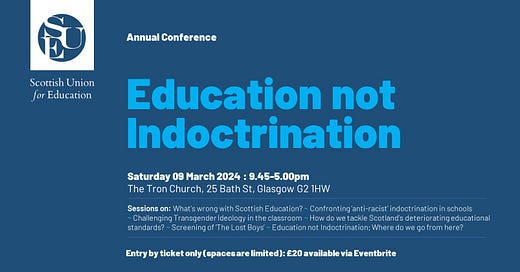

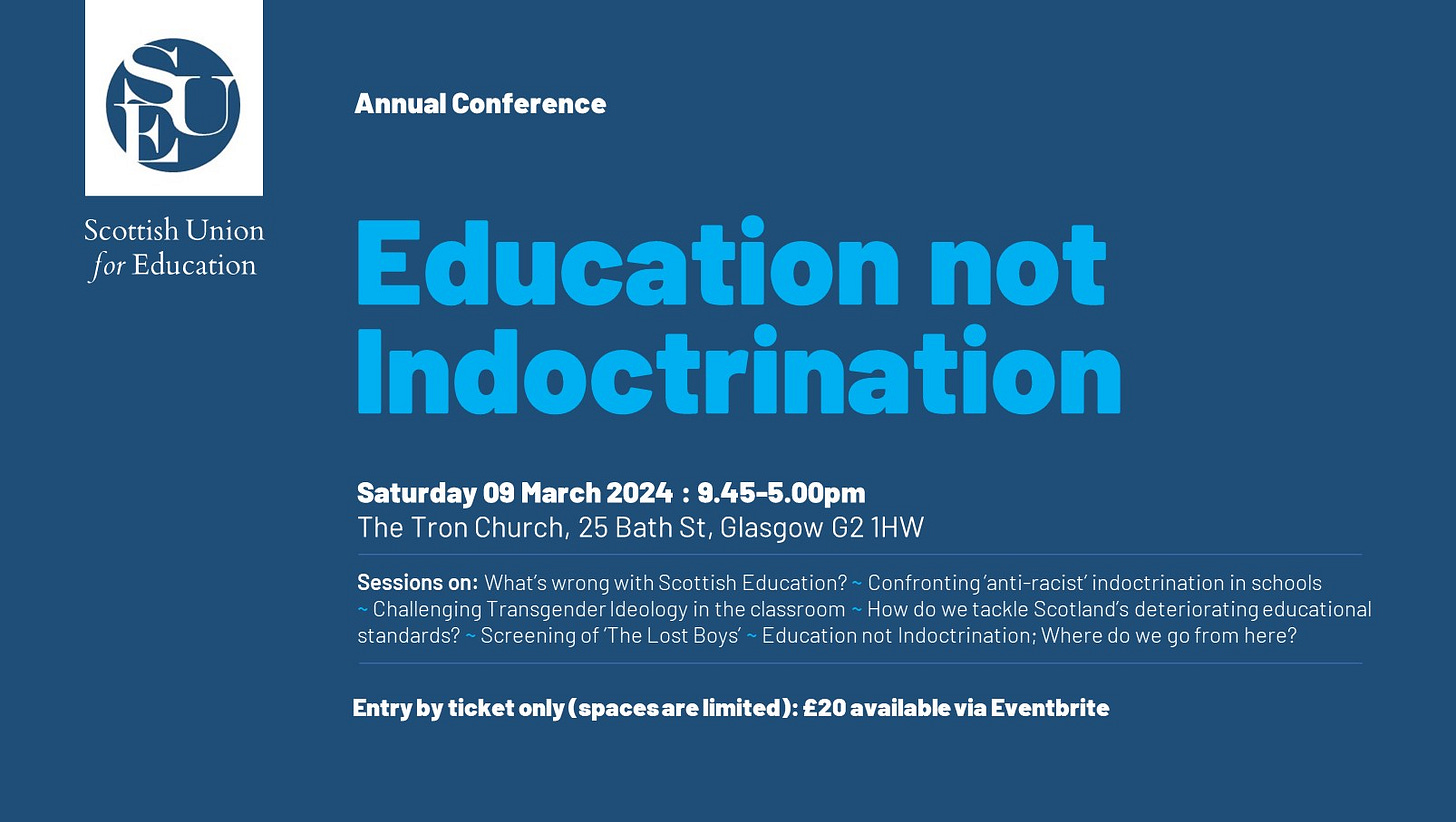

Conference: Education not Indoctrination

SUE is hosting a conference on education in Glasgow on Saturday 9 March. This will include a public showing of the film The Lost Boys, accompanied by a discussion with one of the film-makers. The film explores the lives of men who were encouraged to transition when they were young and examines the reasons why some boys are attracted by the ideas of transgenderism.

Buy your ticket from Eventbrite here

The SNP’s trans crusade will tear families apart

Alex Cameron is a member of the SUE editorial board and producer of the Substack. He is a father of three school-aged children.

Banning ‘trans conversion therapy’ will criminalise parents who want what’s best for their kids.

In Scotland today, conversion therapy is a bit like the Loch Ness monster. Some are obsessed with it, despite there being no evidence for its existence. There are no news stories of electric-shock therapy. No reports of people being sent away to camps to be ‘converted’ out of their sexual orientation. No priests caught keenly ‘praying the gay away’. Conversion therapy simply isn’t a problem in twenty-first century Scotland.

Yet still the SNP-led Scottish government is seeking to prohibit what it calls ‘conversion practices’. To this end, the government last month issued a consultation detailing its proposals for new legislation and criminal penalties. Equalities minister Emma Roddick said [in January] that conversion practices ‘have absolutely no place in Scotland’.

It should be clear that what is driving this ban is not the non-existent problem of gay conversion therapy. Instead, it is being fuelled by the SNP’s embrace of gender ideology. That’s why the real focus of this legislation is a ban on so-called trans conversion therapy, or as the consultation has it, ‘conversion practices relating to gender identity’.

It’s important to clarify what the government means by ‘conversion practices’, which aim to ‘change or suppress ... gender identity’. These practices include ‘talk-therapy, counselling, and certain faith-based practices’. This means that, under the proposed legislation, the act of talking to, or of counselling, a person struggling with gender issues will potentially be prohibited. It will potentially no longer be possible for a therapist, or indeed any other adult, to explore why someone might feel that they have been ‘born in the wrong body’. Instead, adults will be expected to ‘affirm’ any individual who says he or she is ‘trans’.

The Scottish government’s consultation is careful not to use age-specific terms, talking only of the ‘person’. But it is obvious that those the government deems to be most at risk of trans ‘conversion practices’ are children and young people. That’s what makes this legislation so socially corrosive. It would strike at the most fundamental of all relationships – namely, that between parent and child. It would demand that parents relinquish any authority they might have and just ‘affirm’ their child’s self-diagnosis.

This would be a deeply damaging development. Parents ought to be the primary authority in their children’s lives. They are best placed, by a long way, to help their children navigate their way through childhood and puberty and into adulthood, so that they might find their place in the world. Parents are best placed to do this because their guidance comes from a place of love. They only want to help their children.

The ban on conversion practices undermines parents’ authority and stymies their ability to guide their children. In its place, it cements the new elite idea that children themselves are best placed to decide if they should change their pronouns, socially transition, bind their breasts, take puberty blockers, or undergo irreversible, life-altering surgery. And if any parent, therapist or other adult tries to talk a child through his or her issues instead, they can be accused of engaging in ‘conversion practices’.

In some ways, this proposed ban on trans conversion practices is the spiritual heir to the SNPs defeated ‘Named Person’ scheme. Just like that proposal to give every child, from birth, a state-appointed guardian to oversee their wellbeing, the ban on ‘conversion therapy’ undermines parents and impedes their ability to nurture their children free from state intrusion.

Particularly worrying in this regard is the classification of ‘certain faith-based practices’ as forms of conversion therapy. The vague wording could well mean parents being prohibited from raising their children in accordance with their own faith, where doing so is seen to cut against trans ideology. In this way, the ban also poses a threat to religious freedom and freedom of conscience.

There are so many reasons to oppose this ban on ‘conversion practices’. It will prevent confused and troubled children and young people from getting the support they need. And it could set them on a path they will later regret. But the threat the ban could pose to parental authority is surely one of the most compelling reasons to oppose it. At its core, the proposals are anti-family. Like the Named Person scheme, they assume that the family is a cesspit of bigotry from which young people need to be protected by the state.

Concerned parents, religious groups, and ordinary members of the public must engage in this consultation. Together, we can consign this dangerous proposal to the dustbin of history.

This article first appeared in www.spiked-online.com

Report review

Dr Joanna Williams, The Politicisation of History Teaching in Europe: Exploiting the past to promote contemporary concerns. A briefing from MCC Brussels

Rachael Hobbs is a teaching assistant and mother.

Without a collective history, argues Joanna Williams, there is little sense of place or common bonds. This leaves us adrift in a culture of competing identity groups within a one-dimensional present, driven by a new (elite) value system of ‘diversity, equity and inclusion’ (DEI).

Williams, in her review of teaching advisory body the Council of Europe, discusses the erosion of national and world history teaching. Where once the key aim was education and knowledge, today it has become about ‘inclusion’, and in the process, history has become relativised so as to promote ‘minority groups’. Where biases may have existed in the past when teaching history – something that could and was contested – today we find the Council of Europe has no interest in impartiality or the pursuit of truth. In essence, history teaching has been transformed into a therapeutic practice aimed at ‘recognising’ and valorising minorities.

History by its nature is open to different perspectives, and therefore an important academic field to supervise in terms of objectivity. Williams reviews the changing path of the Council, which advises member states on curriculum content, and concludes that there is an increasing emptying out of history to reflect ‘woke’ politics that actually removes knowledge-rich learning.

National history and the European project

The Council of Europe provides history teaching recommendations to countries and carries considerable weight. After 1945, it established that nations should teach their own histories along with a ‘European dimension’ to promote common values in a fragile post-war environment. It emphasised that history played a vital role through building respect between countries. But it also maintained that ‘It is not the work of history to act or provide propaganda for European unity or find solutions to political problems’. At that point in time, history teaching was understood to be important for understanding not only the problems of the past but also the great gains that had come from the European Enlightenment.

Recognising the importance of national sovereignty, during the 1950s the Council reviewed partiality within national texts, to improve quality of resources, but it refrained from propagandising. In the sixties, and increasingly in the 1970s, however, patriotic history was increasingly contrasted to the idea of ‘global responsibility’, leading – critically – towards a new and different type of politicised history teaching.

Influenced in part by migration and multiculturalism in the eighties and nineties, national approaches to teaching were further restricted, and the European Commission Resolution of the Council of Ministers of Education in 1988 recommended that member countries refer more to the ‘value of European civilisation’ within their curriculums.

Williams observes that whereas nations teaching traditional national histories were able to ‘unite citizens in spite of different personal identities’, the EU continued to struggle to promote a coherent idea of the ‘new Europe’. Without this sense of meaning or a cohering sense of history, the EU, helped by the Council of Europe, increasingly promoted itself through the idea of multiculturalism and minorities.

History as ethics

As time went on, the Council increasingly wished to avoid teaching national identity and ‘Eurocentric’ approaches. The Committee of Ministers in the mid-nineties, for example, recommended schools encourage students to consider themselves ‘citizens not only of their country but of Europe and the wider world’.

Policy documents from the time show considerable repurposing of history, proposing ‘a critical approach to historical and present-day events’. As a result, a new presentist approach to history was developed, something that came to disconnect the present from the past, and something that equally disconnected the present from the future. Within this disentangling of time zones, history was becoming less about history, about an understanding of the past and about how this understanding of then and now could help us have a sense of the future. In its place, a new type of ‘history’ was being invented that was centred around the present, where the past was increasingly used as a mechanism for validating modern political beliefs.

Themes under DEI, adopted by the Council in recent years, focus on ‘harm’, ‘othering’ and ‘empathy teaching’. Key topics, such as colonialism, have been condensed to single narratives, rather than teaching what is a multifaceted era of history, worthy of deeper enquiry.

Further chapters in world history have become constricted, and Williams finds neither of the World Wars studied in its own right. There is one Council guide to the Second World War, for example, published within the past decade, called Queer in Europe During the Second World War – a document exploring LGBTQ experiences during the war. This, and many other new stories being promoted by the Council, has no sense of common, collective struggles of citizens but instead project the fragmented identity politics of today onto past events.

Along with a ‘new Europe’, the Council promoted ‘new history’ to ‘approach the topic from every angle, including sexuality and gender’. This, Williams argues, was a way of creating a historical narrative about ‘under-represented groups’. This history is, she argues, more about promoting modern institutions and ideals than anything to do with education or knowledge, or indeed history.

Political beliefs as academic ‘competencies’

By the millennium, there remained a contestation between those who still taught history with some sense of commonality and those increasingly focusing on the politicised sense of minorities. In an attempt to resolve this, the Council developed a new set of ‘knowledge’ and ‘competencies’.

In an attempt to avoid any sense of the promotion of a new set of values, values were now labelled as ‘skills’.[1] Where earlier work of the Council was committed to providing a variety of perspectives to enable pupils to form their own conclusions and develop genuine critical thinking, today, Williams argues, for the Council of Europe, ‘The role of the teacher is not to impart subject knowledge, nor to encourage critical engagement, but to nurture and monitor the presence of desired “behaviours”’.

Competences include ‘Valuing human dignity, human rights and cultural diversity; Openness to cultural otherness, other beliefs and world views; Empathy; Knowledge and critical understanding of the self’. As Williams highlights, these are really opinions that cannot (or must not) be challenged.

‘Empathy teaching’, she notes, further transformed historical issues and event into value-laden themes, something that ‘represents a move away from what students should know to how students should be’.

The notion of ‘lived experience’ also now permeates curriculums, via personal accounts for example, of the Holocaust, based on assumption that students may not emotionally connect to national stories. In this way, Williams argues, events become detached from the collective historical experience, and knowledge about the Holocaust becomes a mere means for students to develop personal ‘empathetic awareness’ – something that is instrumentally connected (in the minds of the educational establishment) to concerns about ‘hate crimes’ today.

Displacement of national identity

Williams shows that in the past, teaching values was implied through acquisition of knowledge. By understanding the past, in all its complexity, one was able to gain a complex and nuanced sense of moral and political issues and qualities. In this way, a knowledge of the past could help the next generation to have a sense of what was, what is, and what could or should be. In comparison, the modern approach to history is based on a projection of present values into the past and a mining of the past for the one-dimensional purpose of supporting these modern concerns.

We can see what this has done to knowledge and history, as the past is turned into a rainbow flag of concerns and issues related almost exclusively to twenty-first century preoccupations with race, gender, sexuality, or disability. As a result, the past has become little more than a canvas of shame, where ideas of enlightened growth – of emerging ideals of freedom, equality and democracy – are lost in a sea of wrongs, in a never-ending world of misery and oppression.

By mining the past through a myopic focus on minority groups and oppression, Williams notes, this approach not only degrades and diminishes the gains of the past but also degrades history as a subject with a sense of development or even with a chronological understanding and a sense of change.

Williams highlights, persuasively, the inevitable chasm between generations that this creates. As she notes, ‘Children taught only what is bad about the past are left alienated from their nation, distanced from older generations who do not buy into such national self-loathing, and estranged from a broader understanding of European culture and enlightenment values’.

Williams is no tub-thumping imperialist who wants a forced history of national pride. Recognising the importance of knowledge as a thing in itself, she calls for a teaching of history that looks at both the gains and the problems of the past, and indeed, the gains and the problems of European history. By focusing on the past through the one-dimensional and historically illiterate preoccupations of the present, the Council of Europe is helping to degrade historical knowledge, undermine the importance of national democracies, and create a generation who are left ‘estranged from the past and alienated from the present’.

MCC is a think tank that assesses European policy on contemporary political, economic and cultural matters. Further information can be found at https://brussels.mcc.hu/

Dr Joanna Williams is founder of the British think tank CIEO and author of How Woke Won.

Her report can be found here .

Note

Set up via the Observatory on History Teaching in Europe in 2020, and within the Council’s paper Quality History Education in the 21st century. Principles and Guidelines (p. 14).

News round-up

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight

Joanna Williams, We need a new kind of politics. Neither Labour nor the Conservative party can challenge woke institutions. 08/02/24

https://unherd.com/2024/02/caught-up-in-the-gender-critical-civil-war/ Andrew Doyle, How I became a target in the gender-critical civil war. A small faction of activists won't tolerate dissent. 08/02/24

https://substack.com/home/post/p-141519883?source=queue Andrew Doyle, Kemi Badenoch Versus the New Puritans. To take on the culture war, we need someone who understands it. 09/02/24

Toby Marshall, Review: The Holdovers. Directed by Alexander Payne, 2023. 09/02/24

https://archive.is/IfVhI Dia Chakravarty . The ‘anti-racists’ want me to hate Britain. This country is one of the most tolerant in the world. But there is a limit to how much a society can take before it breaks. 09/02/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/02/07/no-rishi-sunak-should-not-apologise-for-his-trans-jibe/ Brendan O’Neill, No, Rishi Sunak should not apologise for his ‘trans jibe’. It is the chattering classes’ weaponisation of Brianna Ghey’s death that is truly offensive. 07/02/24

https://substack.com/home/post/p-141371829?source=queue Frederick R Prete, Activists Who Compare Humans To Sex-Changing Fish Don’t Go Far Enough. If gender activists insist on taking life lessons from hermaphroditic fish, they should follow their reasoning to its ultimate conclusion. 10/02/24

https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/education/6366920/why-are-irish-kids-so-far-ahead-of-scottish-pupils/ Calum Petrie, Why are Irish kids so far ahead of Scottish pupils? As Scotland continues to plummet down the PISA rankings, our Celtic neighbour is heading in the opposite direction. The P&J spoke to Irish parents living in the Highlands and Aberdeen to find out why kids in Ireland are outperforming pupils in our schools. 10/02/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/02/11/labours-plan-to-foist-dei-on-britain/?utm_source=spiked+long-reads&utm_campaign=ec39beb26e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_02_11_12_37&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-ec39beb26e-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D Tom Slater, Labour’s plan to foist DEI on Britain. Keir Starmer’s Race Equality Act embodies all that is wrong with woke identity politics. 11/02/24

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.