Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No73

Newsletter Themes: defending civilisation, unconscious decolonial bias at Kelvingrove Museum, and historical truth

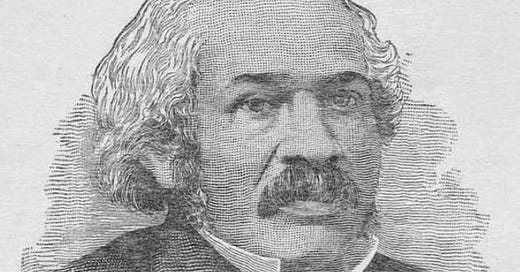

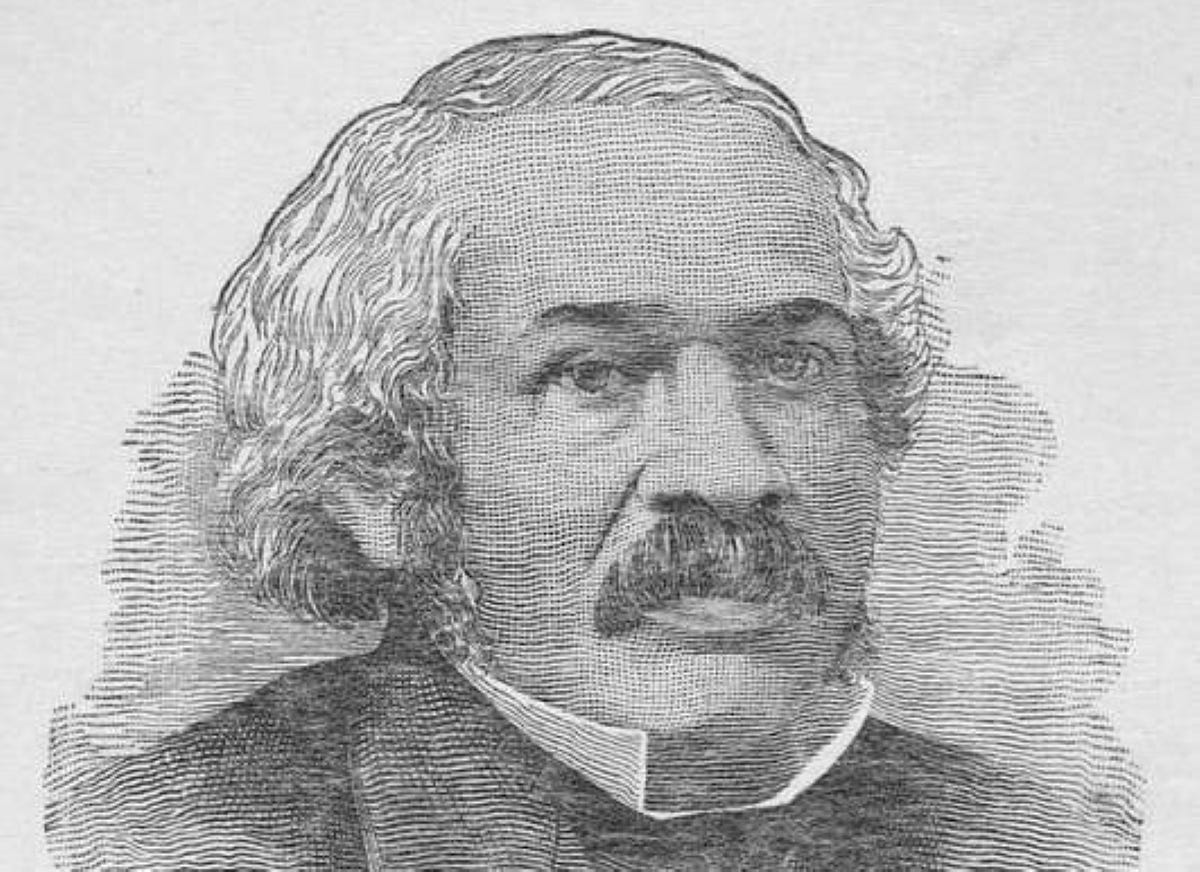

Our new hidden history. James McCune Smith (1813–1865): physician, abolitionist, and public intellectual. Smith’s mother was, in his words, a ‘self-emancipated bond-woman’. Regarding his father, Smith seems to have been a ‘natural’ (i.e. illegitimate) son of a New York merchant who was presumably white, based on Smith’s mention of having ‘kindred in a southern State; some of them slaveholders, others slaves’. Despite being academically extremely able, racial discrimination meant that he was denied entry to American medical schools. Therefore, in 1832, at the age of nineteen, he travelled to Scotland to enrol at the University of Glasgow. Excelling in his studies and having already graduated with a BA and an MA, in 1837 he earned his MD degree, thus making him the first black American to hold the title of ‘doctor of medicine’

PLEASE SUPPORT OUR WORK by donating to SUE. Click on the link to donate or subscribe, or ‘buy us a coffee’. All our work is based on donations from supporters.

A few weeks ago, Stuart Waiton, Chair of SUE, interviewed sociologist Frank Furedi about education. Furedi said that today’s tendency to attack the idea of civilisation poses a serious problem for those trying to teach our children. Since that event, SUE members have been discussing Furedi’s comments. It’s hard to defend the idea of ‘civilisation’ or ‘western civilisation’ if you know a little about the history of the British Empire. Events like the Amritsar Massacre in India (1919), and within my lifetime, Ireland’s Bloody Sunday, make it hard for people like me to use the word civilisation without quotation marks. Gandhi’s famous retort when asked what he thought of western civilisation – that it would be a good thing – has had a strong influence on a several generations of teachers and academics. When we think about civilisation, many of us begin start from a position of scepticism; however, the danger with this approach is that we fail to tell our children about the brilliant acts, thoughts and struggles of our forefathers that helped us to get to where we are now.

This Substack focuses on the debate around the Glasgow – City of Empire exhibition at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow. This new show is a permanent addition to the much-loved museum. You may be planning to take the children to see it over the holidays, or perhaps you have already been. Here’s a warning: this exhibit has not been curated in the normal way – it’s a political polemical rather than a scholarly interpretation. You may need to add to the story it is telling your children to restore an element of balance to their understanding what their ancestors achieved.

Museums are designed to be our link with our past, to enable us to reflect on life and history, and to help us make sense of the present, but this new display reinvents the past to encourage us to take a particular course of action in the present; it’s closer to an election manifesto than a museum exhibition. Normally when a museum curates an exhibition there is an expectation that those in charge have done as much as they possibly could to express what is true and meaningful; however, this norm has been abandoned in favour of a social justice approach to scholarship. At Kelvingrove, the professional curators have hidden behind a group of young people to create a very biased story. If this kind of debased approach to our history is allowed to operate in public museums, it raises question, ‘What we are teaching children in history classes?’

It’s never been more important to talk to children about our history and to ensure that the stories we tell them are balanced and not organised to support a narrow ideology. Parents need to look at what pupils are being taught about industrialisation, the transatlantic slave trade, the Enlightenment, science and technology, and modernism. The process of ‘decolonising’ the museum, and the education curriculum, is one in which we demonise and discredit the actions of whole generations of people. Museums are supposed to be places for enduringly important and valued objects to be stored; they were organised to give us a sense of historical continuity. The assumption used to be that visitors could extract their own thoughts on what these objects represented. By contrast, today’s decolonised exhibits demand that we adopt one story, and consequently a great deal of our history is removed from the picture. On the question of the transatlantic slave trade, the association with the profits of slavery is always in the foreground, whereas those who fought to overthrow slavery, regardless of skin colour, is a minor story that rarely gets told.

Today, we need to revisit the values associated with antiquity – those basic building blocks of civilisation – especially if we want to understand the original purpose of education. The Greeks and Romans relied on slaves, but this doesn’t discredit their cultural output, their philosophy, or the great leaps forward they made in mathematics and early science. We have a responsibility to defend the gains of the past (whether two centuries or two millennia ago) against a form of philistine activism that rejects all the culture and achievements of the past on the grounds that the innovators were oppressive, western and male.

Below, Alex Cameron, parent and design critic, takes a critical look at the Glasgow – City of Empire exhibition and raises important questions about decolonisation. To help you understand the content of the Kelvingrove exhibition, we also provide extracts from a letter written by Nigel Biggar, Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (2023, 2024) to Philippa Macinnes, the Manager at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

The one-sided view of history they describe seems to align with some of the highly destructive campaigning, boycotting and debanking we’ve witnessed over the past week. One Glaswegian told us that children from the Southside had missed out on a work experience week run by Barclays because the bank had been boycotted due to its links with Israel. Meanwhile, Edinburgh International Book Festival has dropped its sponsor, Baillie Gifford, because of the incredibly small percentage of its investments that are in fossil fuels. Children are missing career opportunities and book lovers their events so that others can look virtuous. SUE is increasingly concerned that children are being mobilised by adults, through the schools, to become social justice activists. This is being done against the very spirit of a liberal democratic education system, based on the idea that we should provide pupils with the facts and, as they mature, help them to develop their own judgments.

Penny Lewis, Editor

If you watched the leader debate on STV, you may have noted that education was not on the agenda. We think education should be at the top of the agenda for all Scottish MPs. Sign the petition here and tell us how education needs to change or look for the petition ScottishEducationMatters.

Midnight in the Museum

Alex Cameron, parent and design critic, takes a look at Glasgow’s new City of Empire exhibition.

Glasgow – City of Empire is a new permanent exhibition at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in the West End of Glasgow. The display was cocurated by Miriam Ali, Meher Waqas Saqib and Kulsum Shabbir from Our Shared Cultural Heritage, a youth project supported by Glasgow Life Museums (GLM). Their approach to the objects drawn from GLM is to highlight ‘what it means to decolonise museums’, and to ‘combating the collective amnesia in Scotland regarding atrocities such as transatlantic slavery...’ Kulsum Shabbir wanted to ‘narrow my focus to objects that specifically implicate Glasgow in its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade’, while Meher Waqas Saqib wanted the ‘whole project to encourage people to view the history of Glasgow in a different way, that acknowledges the struggles and exploitation of people of colour’.

Nelson Cummins, Curator of Legacies of Slavery and Empire at GLM, said of Glasgow – City of Empire, that ‘As soon as you start to acknowledge these histories and educate the public on these histories there can be a wider call for action, and I think that’s only a positive thing in terms of not only having a fuller understanding of the past but also addressing some of the present-day legacies of that as well.’

To understand the development of modern Scotland – warts and all – is indeed a vital project. To know where we have come from can inspire us towards a better future. But the narrow presentist and hyper-racialised social justice view – which rests on a binary understanding of the world made up of ‘oppressors’ and the ‘oppressed’ – robs history of its contradictions, dynamism and complexity, and worse, denigrates the contribution Scots have made in the modern era. Glasgow – City of Empire is a bad, narrow, one-sided and racialised reading of Scottish history.

For Nigel Biggar, CBE, Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology and a senior research fellow at the University of Oxford, and the author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, it is a travesty of the truth.

Further, the idea that ‘educating the public’ about the transatlantic slave trade might act as a call to action to fight racism today is a shameful instrumentalisation of history to suit contemporary political concerns. The more the cultural elites say this display is about history, the hollower that claim rings.

By their own admission, this display is not really about engaging with an important historical moment, but rather it is about contemporary concerns of the Scottish cultural elites. It is quite clear that it is about promoting their contemporary political and ideological worldview. The narrative that modern Scotland was built on the backs of slaves and that Britain’s colonial past hangs over Scots today is absurd and just not true. While statues and some street names nod to Britain’s colonial past, they don’t dominate the thoughts and actions of Glaswegians, who simply don’t need trigger warnings (nor did the Glasgow – City of Empire display). Glaswegians are not guilty for the sins of their distant brethren.

Dragging us down an ahistorical one-way street, as Glasgow – City of Empire does, blinds the viewer to other significant forces, nuance, and the rich tapestry and nature of history. It flatlines history and renders it one long, continuous calamity for the oppressed.

The contemporary cultural elite’s approach to history is not to expand our understand of it, but to deep-mine history for the sole purpose of legitimising their ideological outlook. In their hands, this is ‘the end of history’. To them, history is not up for debate – it is binary, it’s a closed book.

While it is of course true that museums in the past represented the outlook of the ruling cultural and political elites of the time, and how they saw themselves, it is no different today. The real curators of Glasgow – City of Empire (Jean Walsh, Senior Curator, Kelvingrove, and the aforementioned Nelson Cummins to name but two) have used and abused their ‘cocurators’ to give a youthful gloss to the idea they are radical outsiders, but their social justice outlook is now mainstream; it is the outlook of the new political and cultural elites in Scotland. They are peddling a wholly destructive ideology that sees the past in binary terms, where no good can be found but only oppression and white supremacy in action.

The idea of the museum’s purpose being to transmit the best knowledge of the past through art and artifacts is being upended in favour of a new role for the museum: to ‘change the culture’ and promote an ever-increasingly narrow and ideological point of view. This is a point of view that runs counter to the existing values and interests of the wider viewing public. But, of course, this is the point. The cultural elites are more interested in ‘educating the public’ through their social justice agenda, while at the same time taking a sledgehammer to traditional Scottish values and mores. From museums to schools and universities, we have political activists recasting the role and function of these institutions. Our cultural institutions should engage, challenge and inspire – not harangue and indoctrinate. Social justice ideology is about ‘controlling the narrative’, not education.

The one-sided and wrongheadedness of Glasgow – City of Empire is just the next phase of Scottish museums shaming the Scottish public through ‘decolonising’ the museum. Scots have way more to be proud of than ashamed about. It is worrying that those with their hands on the levers of cultural power refuse to recognise this fact.

Scottish history is littered with social and cultural highpoints, from the Scottish Enlightenment, educational excellence that was the envy of the world, literary wonders that are read worldwide, great artists and designers, industry and invention. That such a wee country and its people had such an international impact should be an immense source of pride, not contemptuously cast aside and damned.

Modern Scotland was not built on the backs of slaves, but of Enlightenment thinkers, inventive industrialists, and hard-working industrious Scots of all stripes.

Museums in Scotland are leaving the arena of knowledge and culture and instead have embraced the world of politics and ideology. No one will benefit from this.

Extracts from a letter to Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum

Nigel Biggar is Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford and author of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning (2023, 2024). Below are extracts from a longer letter he wrote to Philippa Macinnes, the Manager at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum.

I am not objecting to your museum’s communication of discreditable and lamentable truths about the history of Glasgow and Britain’s Empire. Rather, I am objecting to its absolute exclusion of creditable and admirable truths. The partisan distortion of the past your display presents is so demonstrably extreme as to be tantamount to a lie. Therefore, I urge the Kelvingrove Museum to make itself thoroughly inclusive, telling the whole truth and not just those bits of it that serve an empirically dubious and racially divisive political agenda, uncritically imported from the United States.

On slavery: ‘Glasgow was one of the major port cities in Britain which benefited from the triangular trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas.’ Glasgow – City of Empire

The display misinforms the public by (1) suggesting that Glasgow was a major centre of slave-trading; (2) maintaining complete silence over Glasgow’s leading role in the movement to abolish slave-trading and slavery; and (3) omitting any mention of the costly British (and Scottish) imperial efforts at slavery-suppression worldwide for a century-and-a-half.

According to Dr Stephen Mullen, Lecturer in History at the University of Glasgow, there was ‘a general lack of direct Scottish involvement’ in the slave-trade. ‘In all, there were twenty-seven recorded slave voyages that left Scottish ports, [and] a further four were funded from Scotland... This level of involvement – thirty-one voyages over a forty-nine-year period – is small when compared with prominent slave ports in England, where the trade was much greater and lasted longer’.[1]

The abolition campaign was ‘the first human rights crusade in British history,’ writes Mullen, ‘with an unprecedented mobilisation of public opinion and support’. Scotland played an important part in the initial campaign to abolish slave-trading, sending 185 of the 519 pro-abolition petitions to Parliament in 1792, by when abolitionist societies had been established in five Scottish cities, including Glasgow. The subsequent campaign to abolish slavery itself, which was launched in 1814, elicited a ‘strong’ response in Scotland, which sent 141 petitions from sixty-seven communities, including all the major cities. Notwithstanding resistance from the pro-slavery Glasgow West India Association, overall opinion in Glasgow ‘was firmly behind the abolitionists’. Glasgow University alumni – such as Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, and John Millar – ‘influenced the development of anti-slavery societies globally... and the level of commitment of the later abolitionist movement in Scotland, especially in Glasgow, was a hugely significant factor in promoting an international conscience’.

After abolishing slave-trading throughout her empire in 1807, Britain took the lead in suppressing the slave trade and slavery at sea and on land, worldwide, over the course of the following century and a half. The economic historian, David Eltis, has reckoned the cost to British (and therefore Scottish) taxpayers of transatlantic suppression alone as a minimum of £250,000 per annum – which equates to £1.367–1.74 billion, or 9.1–11.5 per cent of the UK’s expenditure on development aid in 2019 – for fifty years.[2] Moreover in absolute terms the British spent almost as much attempting to suppress the trade in the forty-seven years, 1816–62, as they received in profits over the same length of time leading up to 1807. And by any more reasonable assessment of profits and direct costs, according to Eltis, the nineteenth-century expense of suppression was certainly bigger than the eighteenth-century benefits.

On the abolition of slave-trading and slavery: ‘Persistent uprisings of enslaved people, increasing activism throughout Britain, and more profitable opportunities elsewhere all contributed towards the ending of chattel slavery in the British colonies.’ Glasgow – City of Empire

In this description, the museum’s display diminishes the achievement of the sustained, partly Enlightenment, mostly Christian humanitarian movement to abolish slavery. The British movement to abolish the slave-trade and slavery gathered momentum before the famous slave uprising in Saint Domingue (Haiti) in 1791: the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was established in 1787. While slave uprisings in Haiti and later in Jamaica did garner support and add momentum to the abolitionist campaigns, they did not start them.

The thesis that the British only abandoned slave-trading and slavery because it had become uneconomic is highly controversial, and it is irresponsible of the museum to present it as uncontested fact. Indeed, one American economic historian, Seymour Drescher, has argued that, for the British to abolish the trade when they did, amounted to economic suicide – or, as the title of his book puts it – ‘econocide’.[3]

The British, including the Scots, were among the first peoples in the history of the world to abolish the hitherto universal practices of slave-trading and slavery, and thereafter they used their imperial power to suppress the trade and the institution from Brazil, across Africa and India, to Australasia – at considerable cost in money, naval resources, and lives. Your museum’s display is unjustifiably silent about this.

On racism: ‘Abolition did not mean the end of racism. Racist ideologies that were used to justify enslavement were used to legitimise the colonisation of millions of peoples by the British Empire’; ‘white supremacy’, ‘Our education ... often promoting white racial supremacy. This has contributed to the spread of racist ideas that still shape our lives today.’ Glasgow – City of Empire

The museum’s display implies that, even after the abolition of slave-trading and slavery, the British Empire continued to be simply motivated by the same ‘white supremacist’ racism that had justified them. This is quite wrong. The Christian humanitarianism that dominated so much colonial thinking in the wake of the abolition of slavery was based on the premise of the fundamental equality of all races under God, which implies that such racial inequality as exists is merely developmental, not essential – ‘Whites’ are not destined forever to rule over ‘Blacks’, as ‘white supremacist’ ideology in the south of the United States and among Afrikaners in South Africa held. This Christian view was not generally eclipsed by its social Darwinist rival in the English-speaking world. As Colin Kidd, formerly of the University of Glasgow and now Professor of History at the University of St Andrews, has written:

‘even at the high noon of nineteenth century racialism, theological imperatives drove the conventional mainstream of science and scholarship to search for mankind’s underlying unities. The emphasis of racial investigation was not upon divisions between races but on race as an accidental, epiphenomenal mask concealing the unitary Adamic origins of a single extended human family ... quietly, subtly and indirectly, theological needs drew white Europeans into a benign state of denial, a refusal to accept that human racial differences were anything other than skin deep... Theological factors, more than any others, dictated that the proof of sameness would be the dominant feature of western racial science’.[4]

‘...biological determinism never had the field entirely to itself ... it was scarcely possible to stand in the House [of Commons] to make a speech denigrating a “race”, without someone rising in principled objection to remarks that they considered unBritish, unchristian, illiberal, or just plain prejudiced’.[5] The vigorous persistence of Christian racial egalitarianism throughout the nineteenth century is attested by the fact that the vote was granted to black Africans on the same terms as to whites in South Africa’s Cape Colony as early as 1853, to New Zealand’s Māori in 1867, and to Eastern Canada’s Indians in 1885.

There is no unbroken line of continuity running from the dehumanising racism that justified slavery in the eighteenth century to the present day. The widely popular abolitionist campaign broke it. Consequently, as the Harvard historian of anti-slavery, John Stauffer, has written, ‘Almost every United States black who travelled in the British Isles [in the nineteenth century] acknowledged the comparative dearth of racism there. Frederick Douglass [the famous African American abolitionist, who visited Scotland in 1846] noted after arriving in England in 1845: “I saw in every man a recognition of my manhood, and an absence, a perfect absence, of everything like that disgusting hate with which we are pursued in [the United States]”.’[6]

On the British Empire: ‘British Empire ... engaged in widespread colonial violence and oppression’; ‘The British Empire left a legacy of injustice, pillaging and stealing, with no concern for the long-term impact on indigenous lands and peoples.’ Glasgow – City of Empire

As an overall summary of the British Empire, such statements in the museum’s display are historically insupportable, for at least the following reasons:

The British Empire was among the first states in the world’s history to abolish slave-trading and slavery on the Christian principle that all human beings are basically equal under God, regardless of race or degree of cultural development. It subsequently devoted the second half of its life to suppressing slave-trading and slavery worldwide – from Brazil across Africa, the Middle East, and India, to Australasia – for a century-and-a-half. It liberated slaves, women, and captives by suppressing human sacrifice in West Africa, female genital mutilation in East Africa, suttee and female infanticide in India, and head-hunting in New Zealand. It eliminated famine in India by 1900, according to the Bengali-born economic historian, Tirthankar Roy.[7] Its war against the Boer Republics in South Africa in 1899–1902 was supported by most black Africans and African Americans, because the republics were constitutionally committed to permanent white supremacy. Its war against Nazism in 1939–45 was widely supported by black Africans, not least in South Africa, who were well aware of what they could expect from a triumphant Hitler. It, alone with Greece, offered the massively murderous racist regime in Nazi Germany the only military resistance between May 1940 and June 1941. It provided refuge for millions of Chinese, when they fled war, anarchy, and communism in China by entering voluntarily the British colony of Hong Kong in the 1950s.

On the Kelvingrove Museum: ‘Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum is a museum of empire.’ Glasgow – City of Empire

To be more exact: the south balcony, where the Glasgow – City of Empire display now sits, used to celebrate the truly extraordinary engineering and shipbuilding achievements of Glaswegians during the imperial period, whereas now it damns them all as ‘racist’ and ‘white supremacist’ by association with the British Empire.

References

1. Stephen Mullen, It Wisnae Us: The Truth About Glasgow and Slavery (Edinburgh: The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, 2009): https://it.wisnae.us/. The italics are mine.

2. For an explanation of the method by which the contemporary figures were calculated, see Nigel Biggar, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, 2nd edition (London: William Collins, 2024), pp. 390-1n.63.

3. Seymour Drescher, Econocide: British Slavery in the Era of Abolition (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Caroline Press, 1977, 2010).

4. Colin Kidd, The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 26.

5. Glen Williams, Blood Must Tell: Debating Race and Identity in the Canadian House of Commons, 1880–1925 (Ottawa: willowBX Press, 2014), pp. 27, 29.

6. John Stauffer, ‘Abolition and Antislavery’, in Robert L. Paquette and Mark M. Smith, The Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 564.

7. Tirthankar Roy, How British Rule Changed India’s Economy: The Paradox of the Raj (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Pivot, 2019), p. 130.

News round-up

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight

Andrew Doyle, What does “liberalism” actually mean? Many of those who attack liberalism have failed to define their terms. 29/05/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/05/30/how-smartphones-colonised-childhood/?utm_source=Today+on+spiked&utm_campaign=30c33bbf0f-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_05_30_05_32&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-30c33bbf0f-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D Jonathan Haidt, How smartphones colonised childhood. A toxic combination of safetyism and social media has shaped Generation Z. 30/05/24

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-problem-with-labours-free-breakfast-clubs-plan/ Annabel Denham, The problem with Labour’s free breakfast clubs plan. 31/05/24

https://archive.is/tW5bX Henry Bodkin, 100k special needs children face ‘unfair tax’ with Labour private schools plan, say experts. Vast majority don’t have written certification that would make parents exempt from paying VAT on fees. 26/05/24

https://freespeechunion.org/teachers-could-get-legal-protection-from-blasphemy-claims/ Frederick Attenborough, Teachers could get legal protection from blasphemy claims. 30/05/24

https://archive.is/2024.05.30-022828/https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/puberty-blockers-ban-restrictions-uk-under-18s-5xvpl8f3c James Beal, Doctors may be struck off under new UK ban on puberty blockers. The Department of Health has published emergency legislation preventing prescriptions of puberty blockers from private clinics. 29/05/24

https://archive.is/brOSq Blathnaid Corless, State schools report rise in applications amid fears over Labour’s private school VAT raid. Children are being turned away as parents struggle to find a mid-year space in crowded state schools. 02/06/24

https://archive.ph/nf8f7 Iain Macwhirter, The problem with Kemi Badenoch’s transgender reforms. 03/06/24

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@sue.scot

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at psg@sue.scot

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.