Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No95

Themes: reading literature, child-centred confusion, exclusions and discipline

PLEASE SUPPORT OUR WORK by donating to SUE. Click on the link to donate or subscribe, or ‘buy us a coffee’. All our work is based on donations from supporters.

This week the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) published the ‘findings’ of their consultation on the Scottish set texts which form part of the English curriculum for National 5’s and Highers. The headline outcomes of the consultation are that students will be asked to complete some of the work on their ‘portfolio’ in the classroom, and that some classic texts, such as Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song, will no longer be examined. The decision provoked media attention but little criticism. The Scotsman noted that ‘Nicola Sturgeon’s favourite book’ had been removed from the Higher English list because very few schools chose to teach it.

What is most disturbing about the discussion are the justifications that the SQA gave for making the changes: that ‘learners’ (i.e. pupils) wanted it, or that the text needed to be more diverse or more immediately relevant. Although we are told that a lot of children and teachers were consulted, in the end the summary report seem to be the output of two academics, both from Glasgow University.

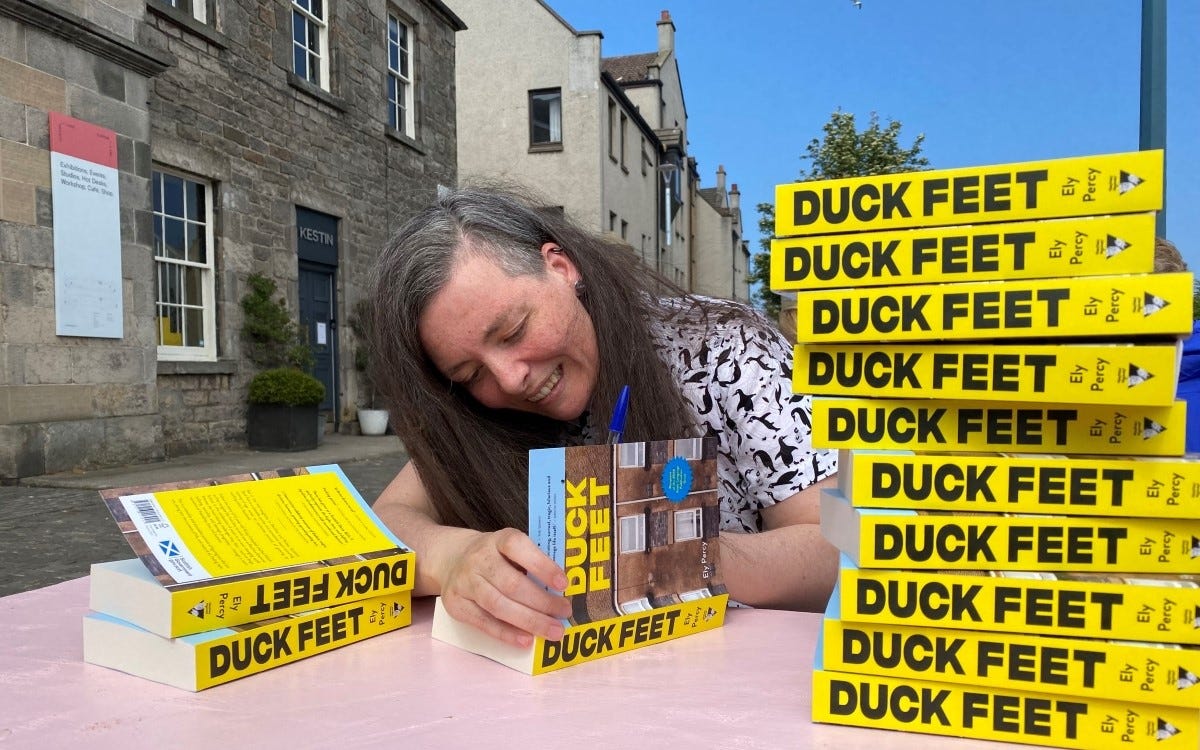

What is clear from the relatively modest changes that were made is that high-quality literature is no longer the foundation of the curriculum content; it is now accessibility and inclusion that matter, alongside personalisation and choice. What do these weasel words mean for children being examined in English? For a start, it means more poetry, because it’s easy to understand and relatable. Added to the National 5 list is just one book: Duck Feet (2021) by Ely Percy, a book by a trans/agender-identifying author about going to school in Scotland. Before you worry about the pressure involved in reading a book in its entirety, the SQA reassures teachers that it’s not necessary to read the entire book because learners will only be expected to read extracts.

The main outcome of the ‘refresh’ is to make English even less demanding for the pupils. Perhaps most shocking is that one of the justifications given for changes in the report is that ‘learners wanted texts which were “easy to remember and to write about” in assessment situations’ (p. 7). Of course they did, and that’s why it doesn’t make sense to ask pupils how they think exams might be improved. Nor does it make sense to further reduce the demands on children in English classes.

As SUE reported back in November 2023, the standard of English set by the National 5 and the Higher exams is already very low. ‘The exams call for no rigour or real learning and, as such, the teaching of the course is superficial and formulaic. I don’t have the statistic to hand, but many students are leaving secondary school functionally illiterate – and some of them have an A in English’, wrote one senior English teacher concerned that we were sending illiterate children out of secondary school with high passes at Higher English. As an SQA marker, the same teacher reported that he had been directed to ignore spelling and punctuation mistakes. He described how a canny student could almost pass one of the papers by simply copying quotes from the text that was supplied.

‘The habit amongst English teachers is to teach an easy poem for the critical essay section of the exam, which is worth 20% of the overall mark. The questions usually oscillate very closely between “Write about a poem that is memorable” or “Write about a poem that is interesting”. Responses usually focus on word choice, metaphor and symbolism, with poetic structure rarely mentioned – low-hanging fruit is sufficient for a good mark’, he wrote.

These latest changes by the SQA are likely to make matters worse. It’s hard not to be cynical and recognise that the reason poetry is so abundant in the current Scottish list is not because Scotland excels at this form of literature but because poems are short and sweet, and that much of the contemporary work is about everyday things – easy to understand and formally uncomplicated.

When our children are not being taught dull contemporary Scottish poems, will they get a chance to read some classics? Fortunately Burns has not been cleansed, but beyond Scottish literature the only other texts that seem to get read are twentieth-century American novels. Outside the Scottish list, the ‘choice’ has been made so open that teachers can select a film or a TV show if they wish. The outcome of this ‘personalised’ curriculum (which is personal to the teacher rather than the pupils) is that our children are lucky if they get one Shakespeare play to read in the lower school, but Dickens, Austen, Shelley, Auden and Eliot may quite possibly be lost to them for the rest of their lives.

In this week’s newsletter, Rachael Hobbs has done some very detailed research on the issue of classroom discipline and school management. We also share a story sent by one teacher about a fictional incident in a fictional school that bears a very close resemblance to their own experience.

SUE’s last online Parent and Supporters Group meeting of the year will be held on Monday 16 December at 7 p.m. Anyone wanting to attend should email SUE’s Parents and Supporters Group at psg@sue.scot.

Penny Lewis, Editor

Children-centred education is undermining teachers

Rachael Hobbs is a parent and an educator.

The rise of disruptive behaviour in class: is ‘child-centred’ education displacing teacher authority?

Last month, the number of exclusions in English primary schools was at a record high. This is alarming in itself, but it is also shocking because until recently, exclusions tended to be at secondary level, suggesting a new crisis among younger children.

Data shows more than 37,000 suspensions in primary schools in just the autumn term of last year – almost as many as in the whole of 2012/13.[1] Persistent disruptive behaviour was the most common reason for suspension or exclusion.

The subsequent debate attributed the problems to causes far beyond the classroom. From an apparent rise in poor child mental health, special educational needs, the impact of Covid lockdowns (still), parents, poverty, resources, and what is termed a ‘complexity of needs’, the focus of blame was on external factors and children themselves.

There was a stark absence of self-reflection, and more importantly, accountability, from education policy makers and experts. No-one thought to look at what is happening within education and to current classroom dynamics.

The modern ‘wellbeing’ and ‘child-centred’ teaching philosophy which dominates is not making the obvious connection between disrupted classes and inhibited pupil learning, within its parameters. This has led to a remarkable separation of discourse between ‘pupil wellbeing’ and academic attainment, as if we must choose between the two, rather than the two issues working hand in hand.

England’s former Children’s Commissioner, Anne Longfield, claimed that a ‘culture of exclusions’ over the past decade had been driven by an ‘emphasis on academic achievement and grades’.[1] It seems unlikely, given the pressure on schools to adhere to inclusion policy and the considerable time it takes to permanently exclude a child. At the same time, Longfield is critical of the focus on achievement, something most of us might indeed consider to be the purpose of education.

Recent figures tell a bigger story given that it takes a long time to reach the stage of permanent exclusion, then for every exclusion you can assume (or know, if you are a teacher) that there has been a lengthy process of disruption to other pupils until such a decision was reached.

Teacher surveys

The survey data on classroom behaviour paints a clear picture that standards and sanctions are not well maintained in many schools.

NASUWT: the teacher’s union

Research conducted by the NASUWT last year through its survey to teachers found the following.[2]

Less than a fifth of teachers (18%) felt that where action was taken against bad behaviour by a pupil, it matched the seriousness of the incident (p. 8).

60% of teachers felt there was misapplication of ‘restorative justice’ policy (where disciplinary measures are replaced by mutual discourse between parties to resolve matters), and that they were ineffective and a significant cause of continued poor behaviour (p. 11).

Around half of respondents (53%) identified a lack of proper policies and procedures to deter unacceptable behaviour (p. 11).

Where respondents specified other reasons, repeated themes were ‘a lack of understanding by pupils of their responsibilities, not just their rights’ (p. 11).

The Union concluded with recommendations that failed to address the issues highlighted. A key recommendation was that every school be able to have a mental health counsellor, effectively making a pathology of poor conduct.

The NASUWT also endorsed ‘wider societal commitments’, including demands for the government to ‘provide free school meals […] to all children from families receiving Universal Credit’ and ‘reverse the decision to remove the £20 per week uplift to Universal Credit and tax credits’, under the claim that there was a link between poverty and bad behaviour (p. 16).[2] This approach lays the blame on children from poorer backgrounds, and fails to recognise that they are just as, if not more, impacted by others’ behaviour.

The report, while it did seek to strengthen behavioural management policy in schools, stopped short of exploring the breakdown of teacher authority in class.

Scotland

In Scotland, the government’s Behaviour in Scottish Schools: Research Report 2023, highlighted low-level disruptive behaviour, disengagement and serious disruptive behaviours frequently experienced by staff.[3]

One of the most common low-level disruptive behaviours was pupils talking out of turn, with 86% of staff having encountered this at least once a day in the past week.

The most common disengagement behaviour was pupils withdrawing from interaction with staff or others, with 43% of staff having had to deal with this on a daily basis.

Most common serious disruptive behaviours between pupils were physical and verbal abuse, particularly physical aggression, general verbal abuse, and physical violence.

Two-thirds of teachers (67%) had encountered general verbal abuse; 59%, physical aggression; and 43%, physical violence between pupils in the classroom in the past week.

Department for Education’s National Behaviour Survey 2022/23

In the Department for Education’s 2022/23 national survey, there was quite a discrepancy between leaders’, teachers’ and pupils’ views on disruption in classes.[4]

84% of school leaders – vs 59% of teachers – reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ in the past week.

Regarding pupils, only 54% reported that their school had been calm and orderly ‘every day’ or ‘most days’ in the past week.

Only 39% of all pupils said that they had felt safe at school ‘every day’ in the past week.

82% of school leaders – vs 55% of teachers – reported that pupil behaviour was either ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in the past week.

Regarding pupils, only 43% said that behaviour had been ‘very good’ or ‘good’ in the past week.

76% of teachers reported that misbehaviour stopped or interrupted teaching in at least some lessons in the past week.

On average, teachers reported that for every 30 minutes of lesson time, 7 minutes were lost due to misbehaviour.

School leaders were more likely than teachers to report being ‘very confident’ in managing misbehaviour (66% vs 35%).

Ofsted

Ofsted, whose report Below the Radar: Low-Level Disruption in the Country’s Classrooms assessed the state of declining behaviour in schools, told us enough in the title of the press release accompanying its publication: ‘Failure of leadership in tackling poor behaviour costing pupils. Low-level disruptive behaviour in classrooms across the country is impeding children’s learning and damaging their life chances.’[5,6] Drawing on 3000 inspections and parent and teacher surveys, Ofsted found the following.

38 teaching days per year were being lost to dealing with disruption.

Typical behaviour problems identified in teacher surveys included pupils making silly comments to get attention, swinging on chairs, passing notes around, quietly humming and using mobile phones.

Two-thirds of teachers who were questioned complained that school leaders are failing to assert their authority when dealing with poor discipline.

Secondary schools posed a greater problem, with the key issue being low-level disruption for teachers and pupils; over two-fifths of parents agreed that their child’s learning was adversely affected.

HM Chief Inspector, Sir Michael Wilshaw, in his conclusion at the time said: ‘I see too many schools where head teachers are blurring the lines between friendliness and familiarity – and losing respect along the way’ and further, called for an end to a ‘casual acceptance’ of persistently bad behaviour.[7]

Crucially, all surveys show predominantly ‘low-level disruption’ among pupils, which does not support widely proclaimed calls for increasing support for mental health issues. Rather, basic issues around teacher authority and subsequent lack of pupil respect for the learning environment are paramount here, but they not opened up for debate.

Pupils with special educational needs or disabilities (SEND)

Feedback from teachers suggests that persistently poor or even violent behaviour is not resulting in sufficient sanction. Compare this with the recent figures on exclusions, showing that it is SEND pupils representing nearly 90% of those permanently excluded in the past five years.[1]

There is no link being made with disruptive classrooms and triggering responses from SEND children, who in order to thrive need, not unreasonably, calm class settings – which you might expect as standard in school. This leaves them at risk of being blamed for becoming distressed if teachers permit chaotic classes as the norm.

In terms of Scotland and similar patterns of disruption in class, former community paediatrician in Glasgow, Dr Jenny Cunningham, states:

As part of an autism diagnostic team together with a specialist speech and language therapist, we would regularly go into primary schools to assess children or attend meetings with staff about them. It was always evident which schools were successfully managing children with additional support needs (ASN). There would be a whole-school ethos and environment that was well ordered, and classes that were structured learning environments, calm and with clear rules applying to all children.

In contrast to less well-ordered schools and chaotic classroom situations, we seldom had to stress how much better children with neurodevelopmental disorders (such as autism or ADHD) coped in formally organised and minimally disruptive settings. These children could access the curriculum, with regular support from ASN staff – and benefit from working with peers as role models (rather than as disrupters).

She expresses concern that staff are widening the parameters of who needs additional support in class due to disruptive behaviour, thus diverting ASN support staff to manage these other pupils rather than the ASN pupils themselves; this inhibits the latter group from having fair access to the curriculum. She ascertains that ‘By needing more personalised learning support programmes for those additional pupils, teachers are lowering their expectations of them’, and concludes, ‘It saddens me that children of normal cognitive ability, including those with neurodevelopment problems, are being denied a full and demanding education.’

SEND pupils thrive in specialist school settings not only due to small class numbers but because of consistent, ordered settings more attuned to their needs. Government policies on inclusion for SEND children in mainstream settings cannot work unless teacher authority and high expectations for wider pupil behaviour are restored.

The stalling of teacher authority

Schools have become very muddled when it comes to authority, with the narrative focused on ‘progressive’, ‘holistic’ education, which seems to be weakening the once-natural call on teachers to first and foremost instil authority in classes. This has left them hesitant in a needless conundrum about taking charge and not ‘harming’ pupil ‘esteem’.

The reluctance to sustain boundaries between teacher and pupil reflects a wider problem with therapeutic pedagogy, which assumes children can operate on a par with adults, in the name of mutual ‘consensus’ teaching. Far from empowering children, this has the opposite effect of sending the message that adults are not in charge, which is detrimental to their sense of security.

Are educators making the mistake of either assuming that therapeutic education means less discipline, or is this what it is, rather unwisely, promoting? Either way, low-level but significant disruption suggests, quite simply, that command and attention of the class are not being held.

If we are making the mistake of equating teacher authority with authoritarianism (two different things), then we are denying children the right environment in which to learn.

References

[1] McGough K, Dunkley E. Primary school pupil suspensions in England double in a decade. BBC News. 21 November 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cz0m2x30p4eo#:~:text=There%20were%2084%2C300%20suspensions%20in,in%20the%20same%20time%20period.

[2] NASUWT. Behaviour in schools. September 2023. https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/static/357990da-90f7-4ca4-b63fc3f781c4d851/Behaviour-in-Schools-Full-Report-September-2023.pdf.

[3] Scottish government. Behaviour in Scottish Schools: Research Report 2023. https://www.gov.scot/publications/behaviour-scottish-schools-research-report-2023/pages/4/.

[4] Department for Education. National Behaviour Survey: Findings from Academic Year 2022/23. April 2024. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6628dd9bdb4b9f0448a7e584/National_behaviour_survey_academic_year_2022_to_2023.pdf.

[5] Ofsted. Failure of leadership in tackling poor behaviour costing pupils. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/failure-of-leadership-in-tackling-poor-behaviour-costing-pupils.

[6] Ofsted. Below the Radar: Low-Level Disruption in the Country’s Classrooms. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/below-the-radar-low-level-disruption-in-the-countrys-classrooms.

[7] Sellgren K. Low-level classroom disruption hits learning, Ofsted warns. BBC News. 25 September 2014. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-29342539.

Everyday experience and fiction

A fictional account of an incident in a fictional Scottish school, inspired by real-life experiences of teachers, as reported to SUE.

‘F*** you’ echoed across the school hallways as Chuck, a wiry S2 lad, directed his ire at our headteacher, Mr Womble. Mr W stood there, his beaming moon face unreactive to Chuck’s outburst. On the noticeboard behind him, a halo of words provided a colourful backdrop to this colourful scene. ‘Skeet Secondary School- school values: respect, responsibility, ambition and inclusivity’, it read.

Indeed, every missive that came from Mr W was full of these key words, and they were included in his response to the angry 15-year-old, as if the presence of the words alone were enough to transform Chuck into a different boy. Last week, Chuck had been one of several of the ‘angry boys’ who chucked chairs across the room in English class.

In the restorative justice session following the chair throwing, Chuck had sat there scowling, no doubt at the futility of the exercise. Chuck knew from experience that he would be placed back in the classroom again following the session.

Last year, teachers had undertaken an ‘inclusivity’ training exercise. They were told to ensure that every lesson was both ‘a mirror and a window’ into every child’s life. Teachers were directed to create maths, languages and history sheets that had to ‘reflect’ back the personal experience of every child in the class.

The sample workshop sheets were full of ‘trans’ Muslim kids in wheelchairs, which wasn’t a mirror or a window for the children at the school, which had a demographic that was predominantly white. ‘I don’t think it would be particularly healthy or helpful to reflect a Chuck back at Chuck. Chuck needed to escape his fractious home environment and look to others rather than himself. ‘We were told we needed to “Get It Right for Every Child” and respect the “United Nations Rights of the Child”‘. But we all knew it was a comfortable lie. ‘It didn’t help Chuck or the other boys like him, that’s for certain’, said one teacher.

News round-up

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight.

Joanna Williams, The battle over the purpose of schools shows woke is not dead. Schools should be about education not indoctrination. 28/11/24

.

https://archive.is/aRozG. James McEnaney, SQA admits ‘fully independent review’ of exam marking never an option. 29/11/24

https://www.pressreader.com/uk/scottish-daily-mail/20241130/281565181324219. Claire Elliot, Literary classic axed for ‘climate’ tale. 30/11/24

https://archive.is/CB6VA. Susie Coen, Students unable to speak with those who disagree with them, says Ivy League chief. Social media has made it difficult for young people to interact with each other in person, the Dartmouth College president said. 01/12/24.

Andrew Doyle, What is a woman? The UK supreme court is currently addressing this ancient riddle, one that has perplexed the greatest minds throughout the ages… 02/12/24.

.

Ben Wright, The disastrous Scottish education trap serving as a warning to Keir Starmer. The decision to move to more ‘skill-based’ curriculums has led to a collapse in results across the devolved nations. 02/12/24

https://archive.is/ZLkuQ. James McEnaney, SQA under fire for ‘unacceptable secrecy’ over survey data. 26/11/24.

https://www.thetimes.com/article/a469221f-f03b-4219-afbf-9c9b31728e30?shareToken=c34c18a2ca9c5568b2e837dcbf77a82c. Iain Macwhirter What is a woman? That’s not a judicial matter. It’s supreme madness for our most senior judges to be debating a question of biological fact. 24/11/24.

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@sue.scot

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at psg@sue.scot

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.

https://open.substack.com/pub/educatedandfree/p/on-good-authority?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=1bl9cq

Much of what's written here rings true for what's happening in our own schools - where did British egalitarians take the idea for comprehensive education and it's progressive ideologies...

Rachel Hobbs insightful article misses one important fact - Scottish state school are (at least for the last 2 years?) now "Zero exclusion zones". The policy began with Looked after children and has branched out to every child.