Scottish Union for Education - Newsletter No27

Newsletter Themes: inclusion policies, lobby groups, and parents’ rights

This week we are including a two-part article from David Buck, an educational psychologist and former Ofsted inspector, looking at how lobby groups are influencing teaching on gender and looking at the impact of this approach on children with special educational needs. Buck argues that instead of making use of long-standing legal frameworks to facilitate the inclusion of transgender children, schools and children’s services are instead adopting the ‘progressive’ policies promoted by lobbying groups – something that is to the detriment of all children. In addition, Lesley Scott, an individual who played a leading role in the campaign against the Scottish government’s Named Person policy, reflects on the government’s attitude to parents and the significance of the Getting it Right for Every Child policy in the development of teaching in recent years.

During July, some SUE members had some informal discussion about what we want to achieve in our campaign work. We know, with a sense of certainty, that we are trying to put education back on the public and political agenda, but we want to see real policy change. The question remains, how can an organisation like SUE make changes in government and school policy? In the USA, parent lobby groups are standing for election onto school boards. Unfortunately, we don’t have that kind of educational accountability in Scotland, but we do need to work out the best ways to hold politicians and headteachers to account. At the end of last term, parents in Glasgow attended the full council meeting; should SUE members start to do this on a regular basis? The best way to enter a dialogue with headteachers is through parent councils, but these tend to be toothless and bureaucratic organisations in which parents’ concerns are rarely taken seriously. Going to parent council meetings and even the meetings of the National Parent Forum of Scotland, a national organisation for parent councils, might be a way to get parents’ voices heard. In the weeks to come the Substack will include some articles about tactics and campaigning. We welcome readers’ thoughts – email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk.

Do no harm

Dr David Buck (CPsychol AFBPsS) is a former local authority educational psychologist and special educational needs Ofsted inspector who now works in private practice running an educational psychology consultancy.

Over the summer there has been a flurry of media coverage on the threat to academic freedom in universities from policies influenced by critical race theory or gender ideology. Less commented on is the impact of similar practices within the public sector, especially children’s support services. This branch of public service has a legal duty to be politically impartial. Nonetheless, ‘woke’ views are often presented by local authority managers as being the only route to the further development of equality, diversity and inclusion in educational settings. Frontline staff are often expected to accept these politically contested positions without challenge, and an illusion of impartiality is maintained simply because no other approaches are considered.

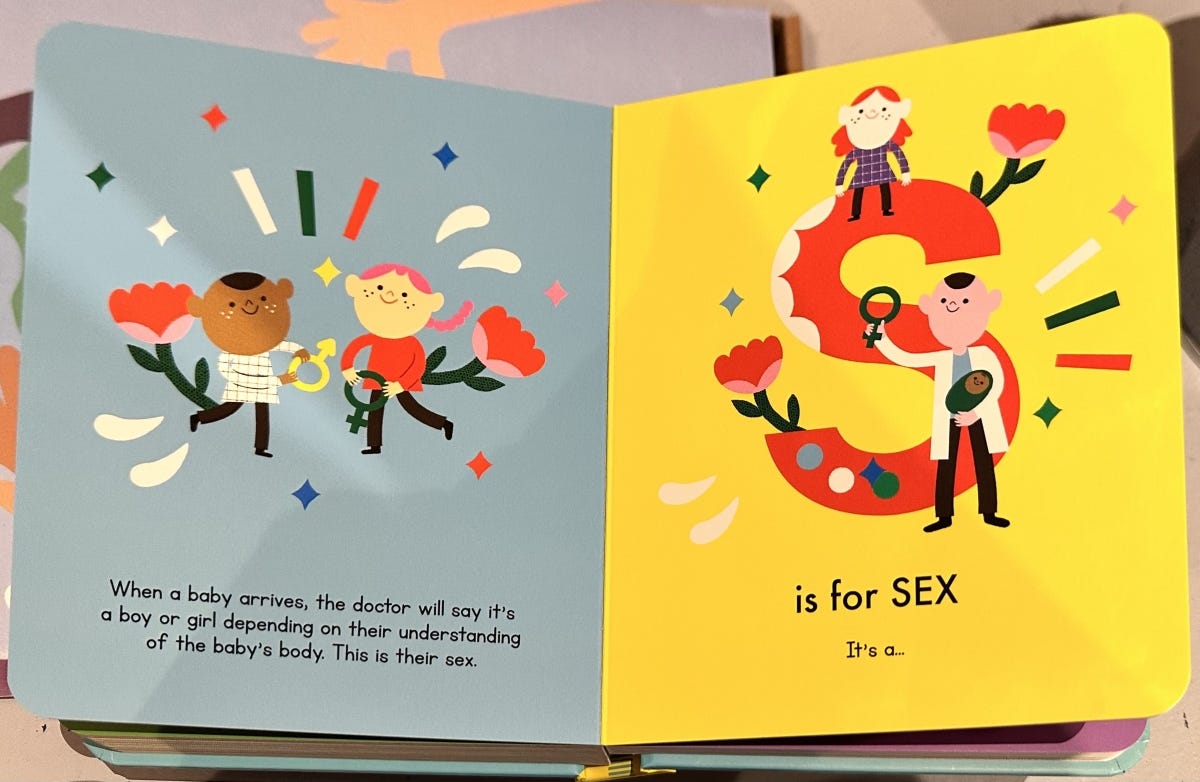

Tensions within children’s services between the duty of political impartiality and partisan, contested policies promoted by managers are now having a significant impact on frontline practice, particularly in relation to the needs of transgender children in educational settings. Local authorities and schools themselves have sought advice from transgender activism charities, such as Stonewall and Mermaids, that are often uncompromising in their project to dissociate gender from biological sex. They have developed ‘transgender toolkits’ that go far beyond the needs of any individual transgender students to promote a broader ideological stance on gender and sex. For example, such toolkits often recommend whole-school adaptations to single-sex spaces and sports, teaching that sex is on a ‘spectrum’, and even school policies on ‘chest binding’ (i.e. the use of constrictive bands to flatten the breasts).

Many public sector frontline service staff have noted managers and human resource departments gradually adopting woke values into their policies. This appears to have happened because charities and campaigning organisations provide easy-to-follow, ready-made rules along with off-the-shelf moral authority. The delusion of moral authority seems likely to have contributed to the errors local authorities made in recent child protection scandals in Rotherham, Rochdale, Telford, Aylesbury, Oxford, Derby, Halifax, Keighley, Peterborough, Huddersfield and Manchester.

Woke values are put into operation without consulting the frontline service staff who are tasked with their implementation. In schools and children’s support services, received wisdom assumes ‘doing nothing’ is the same as ‘doing no harm’, despite historical warnings relating to ‘omission bias’. As Hannah Arendt noted: Where all are guilty, no one is; confessions of collective guilt are the best possible safeguard against the discovery of culprits, and the very magnitude of the crime the best excuse for doing nothing. In schools, this can result in what amounts to the inculcation of a moral imperative untested by democratic accountability. This is especially concerning when services dedicated to child protection take on board, without challenge, a particular view in relation to gender identity. Vulnerable children risk having new gender identities affirmed, leading to irreversible medical decisions with lifelong fallout. These dangers bring to mind scandals in places such as Rotherham, where local authorities were specifically accused of an inability, at the time, to challenge the repeatedly raised child protection issues relating to grooming gangs, for fear of appearing racially motivated.

Many frontline staff are increasingly concerned about their local authority’s apparent indifference towards any wider stakeholder consultation on transgender issues, including with parents. Of particular concern is the way that protagonists of gender ideology react to criticism, often adopting a dogmatic, semi-religious dismissal of any dissenting voice, forming a barrier even to alternative conceptualisations, let alone whistleblowing.

Unfortunately, the complacent approval of woke values seems to help the career progression of senior managers while maintaining culturally privileged group membership for their compliant staff. In local authorities, holding particular values has long been a way to establish tribal differentiation between managers and frontline workers and between public services as a whole and their respective client groups. Put more crudely, woke provides a management tool to maintain division between oppressors and oppressed.

Remaining silent, the assumption that ‘doing nothing’ is the same as ‘doing no harm’, when it comes to transgender children, could come to be seen as reckless, as it was in the examples of the child protection scandals cited above. Psychological and other ‘wellbeing’ services might wish to reflect on the risks involved in tacitly supporting under-16s who embark on a ‘Gillick pathway’ to irreversible decisions that they may well regret in later life (a responsibility for which that they singularly maintain if parental views are not included).

Psychological services that uncritically choose their manager’s woke narrative not only expose children to these risks but leave parents responsible for a lifetime supporting their child as a seriously ‘self’-harmed adult. Rather than ‘doing nothing’, at least some moderation might be offered. This could entail discouraging the individual schools, support services, and staff members who act as ‘trans activists’ and may be missing the real child protection needs for which they are formally responsible. Psychological services could also give voice to the increasing evidence of the correlation of transgenderism with autism (see, for example, Dattaro 2020). This would enhance strategies already well established for the wider brief of inclusion that have been developed in educational settings, especially since the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014.

Reference

Dattaro L. 2020. Largest study to date confirms overlap between autism and gender diversity. Spectrum. https://doi.org/10.53053/WNHC6713.

Inclusion, lobby groups and special needs

Dr David Buck (CPsychol AFBPsS)

Educational settings have a well-established assessment procedure for children with special educational needs (SEN) such as sensory impairments, autism, and learning, emotional, behavioural, language and social communication difficulties. This is the multidisciplinary statutory assessment procedure, which used to refer to a process that ended with the local authority setting out a Statement of Special Educational Needs. Originally laid down in law by the Education Act 1981, after several updates it now refers to making an Educational, Health and Care Needs Assessment and a commitment by the local authority to provide resources specified within an Educational, Health and Care Plan as required under Part 3 of the Children and Families Act 2014. In both cases, the statutory assessment process required at least five sources of evidence to be submitted in order to assess the SEN and determine the resources necessary to meet them. Therefore, this remains a broadly equitable process across the country.

The current Educational, Health and Care Plan paves the way not only for more scrutiny by and between professional agencies but also more democratic accountability than the postcode lottery of local support groups that are susceptible to the influence of transgender activism charities such as Stonewall, Mermaids and Gendered Intelligence. The Weberian bureaucracy inherent in the statutory assessment of SEN could form its own ‘paradoxical intervention’ by slowing down decisions made in haste and providing a broad platform where outlier perspectives stand more chance of being heard and strident charities side-lined. Statutory assessment has particular relevance to supporting the exceptional needs of children struggling with their gender identity in educational settings.

This works in three distinct ways. First, statutory assessment is, of course, just the sort of bureaucratic channel along which woke values could actually be promoted in the public sector. However, the process also has form in moderating the excesses of some virulent campaigning agendas. For many years the powerful dyslexia lobby adapted the deficit-hunting tendencies of public sector support services to help self-identify (via parents) children as dyslexic rather than having learning difficulties. Teachers were often just as keen to shift responsibility and mask inappropriate teaching methods by labelling children as having dyslexia.

Over time, the effect of channelling disputes about dyslexia resources through statutory assessment procedures has had a moderating influence on the often overzealous lobbying charities. This also had the parallel effect of raising the visibility of research revealing that better literacy teaching methods had evolved. This demonstrates not only just how unhelpful charity involvement in complex pedagogical issues can be but also how useful statutory assessment can be in mounting a challenge. In a similar manner, statutory assessment can formally confront the excesses of the transgender lobbies and promote consideration of the research that indicates autistic components may well be present in each transgender case under assessment.

The second way in which statutory assessment has particular relevance to supporting the exceptional needs of children struggling with their gender identity in educational settings is with regard to children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. The Children and Families Act emphasises interagency cooperation and the wider context of a child’s difficulties in relation to the curriculum and whole-school environment. It balances the needs of the SEN child with the impact on their peers. The enhanced agency cooperation and contextual framework of statutory assessment can encourage discussion and support for the full breadth of implications of transgender children’s needs in educational settings.

Third, the evidence from the professional reports required for statutory assessment are specifically commissioned by the local authority to be produced without commentary on the resources required to meet those identified needs. Local authorities that promote an almost universal mainstreaming policy for SEN will not necessarily see this as political. However, they would immediately do so if segregated provision was allowed to be directly recommended by a psychologist, medic, social worker or other professional, due to the increased costs that would be incurred. Nevertheless, all stakeholders have an unrestricted voice, regardless of employing authority’s guidance, at SEN and disability tribunals through the appeals procedures.

Although often regarded as a slow bureaucratic process, statutory assessment has provided oversight of the equitable allocation of resources required for each of the clearly defined categories of SEN. This stands in marked contrast to the developing definition of transgenderism almost entirely reliant on ‘self-identification’. Statutory assessment enables practitioners to discuss and support transgender individuals’ needs in educational settings more fully and in an independent manner, thereby enabling local authority representatives to appreciate the wider ramifications of these issues, especially at SEN tribunal hearings. Therefore, the statutory assessment process can provide frontline children’s services staff with more of a distance, when necessary, from bias, whether this originates from local government guidance, lobby groups or transgender activism charities.

Meeting the needs of transgender children

Special educational needs, as an educational construct, has developed over many years to reach beyond the individual ‘within-child’ factors of its earlier manifestation. It now includes issues of ‘segregation’ versus ‘mainstreaming’, ‘least restrictive environment’, ‘disruption of others’ learning’. But it has not (yet?) fallen victim to the extreme expressions of identity politics. Transgenderism, in contrast, has been redefined so as to encroach on some of the most basic questions of personal identity. In an educational context, this has a significantly negative impact on the curriculum and the whole school community by claiming access to girl’s single-sex places and sports and contradicting basic biological facts.

Schools need their own in-house procedures to limit the socially disruptive demands of transgender activism. Schools are bound by political impartiality, as UK government ministers have recently restated. Statutory assessment processes could be utilised to emphasise this duty for transgender issues arising in educational contexts and formally expose the local authorities’ promotion of woke values as anything but ‘impartial’. It could provide something of a counterweight to the omnipotence of those charities that make self-interested claims based on their own interpretations of their clients’ ‘lived experience’, regardless of the effects on the hard-won rights of others.

Statutory assessment procedures can help meet the needs of transgender students in schools by offsetting powerful charity lobbying; allowing for an assessment of wider contextual elements related to the needs of all children to be taken into account; and allowing frontline workers the opportunity to challenge, with relative impunity, the supposedly politically impartial local authority consensus and break from a blind adherence to local authority policy, as necessary.

In school settings, there will of course need to be continued efforts to recognise the complexity and sensitivity of transgender issues and assert a firm stance against disrespect. There needs to be a way to support such children in school with strategies that challenge open bigotry towards them but does not further confuse them with the denial of biological difference on which the current (Stonewall) approach is founded. These and other strategies will parallel many already in place in the educational setting. Existing school policies on child protection, diversity, inclusion and anti-bullying are likely to comprehensively meet any outstanding needs.

Current policy requirements more than adequately meet the needs of transgender children in school settings. Limiting the identitarian qualities within SEN to the pragmatics of matching need with resources will avoid a future backlash caused by complacency towards open debate of difficult questions.

Getting it wrong for every child

Lesley Scott was Scottish officer and trustee for the charity The Young ME Sufferers (Tymes) Trust, which was part of the successful legal action against the Scottish government to overthrow the Named Person legislation, and she was active in the NO2NP campaign.

For decades, the state has tried to destabilise the family and insert itself between children and their parents, because by doing so, it can fashion the generations to come without the ‘subversive, varied influences of their families, and indoctrinate them in their rulers’ view of the world’; this quote comes from the UK Supreme Court judgement of 2016 in ‘The Christian Institute and others v The Lord Advocate (Scotland)’ given by Lady Hale, Lord Wilson, Lord Reed, Lord Hughes and Lord Hodge.

This judgement, given on 28 July 2016, effectively brought an end to the Scottish government’s Named Person provision contained in the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014. The Named Person provision was intended to provide a single point of contact for parents and families to access help and support. However, as the detail of the legislation was examined, it became clear that rather than helping the minority of children and their families who desperately needed assistance, it was going to make that help even harder to get by labelling every child in Scotland, from third-trimester pregnancy to 18 years of age (26 if they had been in care) as having wellbeing needs, thus making the haystack bigger and the needle harder to locate. The 2016 judgement from the UK Supreme Court stated the functions of the Named Person to be what they considered ‘appropriate in order to promote, support or safeguard wellbeing’. It then went on to state that ‘‘‘Wellbeing’’ is not defined’.

Wellbeing was to be measured through the Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) policy using the Safe, Healthy, Achieving, Nurtured, Active, Respected, Responsible and Included (SHANARRI) indicators.

According to 200 SHANARRI risk indicators, there was a risk to wellbeing if, for example, the child was under 5 years old; there was illness within the extended family, experience of bereavement (including the death of a pet), or parental resistance or limited engagement with the Named Person; the parents had a different perception of any problem; or a child did not get the bedroom decoration they wanted.

While it was stated that access to a Named Person was an entitlement to ensure that a child, young person, parent or family member had someone whom they knew, to approach for help or advice if they needed it, the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 placed a statutory duty on the Named Person, regardless of the child or parents’ views or consent to actively ‘support, promote and safeguard’ the wellbeing of every child in their care. Thus, the role of the Named Person was a proactive one, not a pastoral role, not an opt-in on the part of the child/young person/family as and when they felt they needed or wanted it, as it had been advertised.

Every sector of the state was, through the Named Person, to have access to every child, and therefore every family’s personal, confidential information. The Named Person legislation made it statutory that health, education, police and other bodies send private information to the Named Person about children’s wellbeing without asking for parental consent or even making them aware that information sharing was taking place.

This was to be enabled by lowering the existing threshold for information sharing from ‘welfare’, the ‘risk of significant harm’, down to ‘wellbeing’; but there was, and continues to be, no definition of ‘wellbeing’, leaving children, young people, parents and families at the whim of social trends, state sector bias and gut feelings.

Stuart Waiton, senior lecturer at Abertay University and now Chairperson of SUE, spearheaded the response to this attack on the sanctity of the family unit. The Christian Institute, Alison Preuss (Founder of the Scottish Home Education Forums), Maggie Mellon (independent social services consultant), Dr Jenny Cunningham, Tymes Trust, and many other groups, individuals and families up and down the length and breadth of Scotland stood with Stuart against this totalitarian move by a democratically elected government.

Legal papers were lodged but Edinburgh’s Court of Session failed to understand the dangers posed by the legislation, forcing the challenge to be taken to the UK Supreme Court, where, in an historic ruling, the UK’s most senior judges unanimously ruled that the Named Person provision was unlawful in key aspects, adding; ‘The first thing that a totalitarian regime tries to do is to get at the children...’

By getting at the children, the state replaces the family, indoctrinating the generations to come and removing all challenge to its ambition. In 2016, the then Minister for Children and Young People, Aileen Campbell, infamously stated that ‘parents also have a role’ in the raising of their own children. This illustration of the authoritarian presumption of the state’s agenda assumes the state’s primary role and, worse still, presumes the right to grant parents a secondary role in their own children’s upbringing. The public response to this arrogance led to Ms Campbell being known henceforth as Aileen ‘Also’ Campbell.

So, the Scottish government had lost in the legal arena and also in the court of public opinion. Nevertheless, they still refused to acknowledge the fact.

Following the Supreme Court ruling, Named Persons were rolled out across Scotland on a non-legislative basis, leaving parents and families still subject to the fickleness of state employees but without any legal framework to challenge the postcode interpretation of this oppressive onslaught against families. The fight continues.

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.