Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No34

Newsletter Themes: why children’s rights are wrong, the disappearance of childhood, and how to understand adult-imposed environmental catastrophism

Welcome to the Scottish Union for Education Substack. This week Stuart Waiton takes a look at the idea of children’s rights, explaining how the invention of this seemingly progressive idea has helped lead to a situation where the state and modern elitist activists have come to determine the nature of childhood; Simon Knight explains the historical emergence of the idea of childhood and warns that today we are losing both a sense of adulthood and childhood; and lastly, Alex Cameron explains how political environmentalism has become a burden of limits placed, by adults, on the small shoulders of children.

As Graham Linehan hits the headlines again, following the praise given to his new book by Richard Ayoade, we are delighted to be hosting a discussion with Graham about his life, his work, and the experience of being cancelled by the intolerant trans-obsessed establishment. Tickets are available here – get yours early before they sell out.

All proceeds from the Graham Linehan event will go towards helping parents and supporters campaign for their right to protect children from indoctrination. If you would like to get involved, contact Kate Deeming at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk.

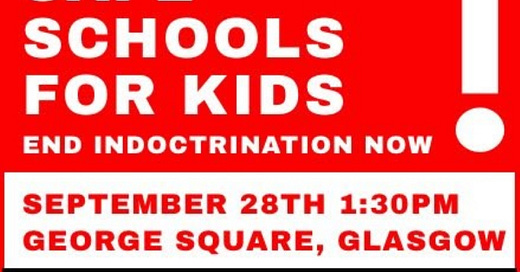

On Thursday 28 September at 1.30 p.m., there will be a rally at George Square, Glasgow, against indoctrination in education and the harmful promotion of transgender ideology to children. The rally has been organised by the brilliant Parents Watch Education Glasgow group to coincide with a meeting of Glasgow City Council, who will be discussing and promoting LGBTQI++++ education in schools. All welcome.

Children’s rights, wrong

Stuart Waiton is Chairperson of the Scottish Union for Education

Approaching the turn of the millennium, James Heartfield wrote an article for LM magazine called, Why are children’s rights wrong? In it, he noted the contradiction of talking about ‘rights’ in the context of children. His warning about the potential dangers of this approach have never been more important.

I read this article at the time of publication but had forgotten, as Heartfield noted, that it was none other than Hillary Clinton, now infamous for calling Trump supporters a ‘basket of deplorables’, who had promoted the idea of children’s rights in an essay written in 1974 called Children’s Rights: a legal perspective.

In 1989, the Children Act was passed in the UK, and by making the child’s welfare ‘the court’s paramount consideration’, the interests of the child were held to take precedence over the rights of parents.

Clinton’s logic that society should start from the assumption that children are legally competent had a progressive ring to it, but as Heartfield notes, it was the same argument being made by the Paedophile Information Exchange. Clinton clearly had no intention of going down this road, but the logical question remained: If we accept a child’s competence before the law, why not in sexual relations as well?

As well as this potential confusion between adulthood and childhood, helped by the idea of children’s rights, Heartfield had one eye on the way that this approach risked handing authority not to children, who lack the maturity to exercise it, but to so-called ‘experts’ and professionals who feel they know better than parents what children need.

Interestingly, at that time, Heartfield noted without hesitation that it was obvious that children do not have the right to watch what they want on television. Perhaps unsurprisingly, even here in Scotland at least, we have had questions raised about this. During the Scottish government’s promotion of its Named Person scheme, leaflets incorporating the children’s rights approach explained that respecting your child means that ‘your child gets a say in things like how their room is decorated and what to watch on TV’. Following this logic, limiting what your child watches on television could be a ‘wellbeing concern’ that needs to be recorded and shared by right-thinking experts!

Perhaps most importantly of all, Heartfield noted that through the process of defining children’s rights as rights that are protected by the state, the very idea of individual rights was being degraded, thus moving the idea of rights away from an understanding of individual freedoms to new forms of rights as protections. If these are the sorts of ‘rights’ that the rest of us should expect, he noted, ‘then we had better get used to being treated like children’.

The Children Act helped to develop the framework for the state to act as super nanny, and depending on how the wind is blowing in the world of politics, Heartfield noted that this could lead, as it had done in America, to a lesbian mother losing custody of her child by denying the ‘right’ to a ‘normal’ upbringing.

Today the wind is blowing in a different direction, and the Scottish state is considering whether or not to create a ‘conversion therapy’ law that would make it illegal for the same lesbian parent to deny her child’s ‘right’ to determine his or her ‘gender’ identity.

Consideration of a child’s welfare, Heartfield observes, ‘often becomes a means to pass judgement on an adult’s lifestyle’, where the parent, ‘soon finds that his or her private life is the concern of the child-obsessed courts or social services’. Thus, children’s rights act as a convenient fiction for the authorities, who have a blank page on which they ‘can write down whatever prescription they deem appropriate’.

The Children Act and the invention of children’s rights is a classic of its time, where a progressive, caring and liberal-sounding initiative emerges that disguises the authority’s domination through the language of liberation.

Today, we find that the blank page of ‘liberation’ has resulted in new elites’ promotion of ‘gender’ identity. In Only Adults? Good Practices in Legal Gender Recognition for Youth, we find a front cover with an image stating ‘Trans rights are human rights’. In this document, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child is used to note that ‘the child’s best interest requires recognition of a separate legal personality, as well as the right for one’s separate viewpoint to be heard’ (p. 13). Consequently, the instruction is given for states to ‘take action against parents who are obstructing the free development of a young trans person’s identity in refusing to give parental authorization when required’ (p. 14).

With a growing number of confused children being encouraged, both online and by our education authorities, to embrace the idea that sex is fluid, our new ‘experts’ are there at hand with their children’s rights handbook, emboldened to determine what is best for all children in Scotland.

Elsewhere, we find the confusion of adulthood and childhood being played out in primary schools, with sexuality education understood within the context of rights and identity. And we find the new Scottish Human Rights Bill, now under consultation, talking about the ‘right to a healthy environment’ and the ‘right’ to live free of racism. Both sound progressive and liberating while incorporating a level of contempt for the ‘prejudice taught to us by the older generations’ (p. 25).

Through all this, the language of children’s rights comes to mean the authority of the elites to increasingly determine what is right and wrong for our children. In the process, parents and grandparents – the very people who look after and love children – are cast aside, often labelled as the equivalent of Clinton’s ‘deplorables’.

Rights, properly understood, are freedoms that only adults can exercise, free from the state, not freed by it. They provide a liberal and truly progressive framework for all of us to speak our minds and to raise our children in accordance with our own beliefs and values. They allow us to associate with whomever we wish, to set up groups of like-minded individuals who can make themselves heard over the confused din of ‘expert’-enforced ‘rights’.

If you would like to join us and to exercise your rights, get in touch with Kate Deeming at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk.

Children, not mini adults

Simon Knight has a PhD in Education from the University of Strathclyde. He has been working with children and young people in a variety of social care, youth work and school contexts for 35 years. He has two school-aged children.

Children are a special class of human requiring protection both from the rest of society and from themselves. The distinction between children and adults came to fruition in the nineteenth century, when the progressive ideas of the Enlightenment developed alongside the practical necessities born of the Industrial Revolution. During most of the past 200 years, Western societies have increasingly accepted this progressive distinction, and it has afforded children protections and the space they require to grow up successfully.

By contrast, in many of the current discussions around childhood and education, the category ‘childhood’ is understood pejoratively, as an oppressed circumstance forced on to a minority group. This discussion results in a blurring of the distinction between children and adults, opening children up to various unreasonable expectations. For example, ‘age-appropriate’ sex education is not what the new Relationships, Sexual Health and Parenting (RSHP) curriculum is demanding of schools; today’s modern teacher is being encouraged to be ‘open’ with children about sexuality, and the result is an increasingly unhinged sexualisation of children.

Problems become social

The seeds to an understanding of society’s foundations based on human actions, rather than ordained by God or nature, were sown during the Enlightenment, but these ideas came to fruition during the nineteenth century. While the Enlightenment was predominantly an intellectual explosion underpinning the development of a rationalist approach to progress, the nineteenth century developments such as population and health mapping in London or factory working legislation began to politicise this social understanding of history.

During this time, many frameworks were established that wrestled with the causes of social problems such as poor living conditions for working adults and their families. The trend towards social survey work also supported the evidence base for social understandings and implicitly human control of the world. The consequent dramatic increases in government interventions during this time, exemplified by the numerous Acts regulating child labour, indicate that human action was now established as the generally accepted method of alleviating distress.

If we turn our attention from the dynamics behind poverty and politics to understandings of children and childhood, we can see that the ‘social’ remains pertinent. For writers such as Hugh Cunningham (2006) [1], it was clear that childhood was also a social creation, something that had been ‘invented’ over time.

Similarly, Philippe Ariès, in his book Centuries of Childhood [2], explains how pre-modern children outside of the elites simply followed their parents to become labourers at a young age. In those times, we found the existence of ‘infants’ but not of children or childhood. In medieval times, for example, children lived in an oral world and reached the ‘age of maturity’ at seven, and in many respects, thereafter, became mini adults.

Postman, in The Disappearance of Childhood [3], explains that the separation of adulthood from childhood took place from the mid fifteenth century, helped by the invention of the printing press and the creation of an educated adult who now developed a level of complexity and knowledge unavailable to children.

Humans as public and private persons

For Postman, the way to understand childhood was to understand the prior emergence of the modern adult; the emergence of a literate, educated individual who had a civilised sense of what was public and what was private.

This separation of public and private life that emerged over time was important for also separating adult life from the lives of children, who, it was increasingly understood, were too immature to be incorporated into this public world. As Postman and others note, developing a consciousness that certain ideas, actions or behaviours are not useful for children to be party to is adulthood’s initial ‘moral content’.

This moves on the understanding of children as somehow lacking in relation to adults: a deficit model of childhood, if you like. As not being able to comprehend or assimilate certain information or be able to act on it in a responsible manner. In her paper The Legal Construction of Childhood (2000) [4], Elizabeth Scott succinctly sums up the modern approach, noting how children ‘are innocent beings, who are dependent, vulnerable, and incapable of making competent decisions’ (p. 2).

From this standpoint, it came to be understood that children are ‘unable to exercise the rights and privileges that adults enjoy, and thus are not permitted to vote, drive, or make their own medical decisions’ (Scott 2000, p. 2). Further, ‘children are assumed to need care, support and education in order to develop into healthy productive adults’ (Scott 2000, p. 2).

In a modern democracy, laws need to be generally applicable because clear demarcation is required as to when they apply and when they do not. In the case of children, generally assumed to be incompetent, there needs to be a point at which they can be treated as adults. Before this age, children are deemed not to be responsible for their actions, incapable of wrong or doli incapax, and therefore cannot be held to account for their actions.

Childhood was (and is, or should be) a time and space to develop into an adult; only as an adult, an individual with a certain level of maturity, can we talk about ‘self identity’. As Mitterauer argues, ‘Childhood and youth are seen as the dynamic age of life. The adult, on the other hand, is the individual who has found himself’ (Mitterauer 1992, p. 27).

Today, we find all sorts of confusion when it comes to the question of adulthood and childhood. As we have seen already in this Substack, the idea of children’s rights has helped to degrade the idea of adulthood. Indeed, what we are witnessing in education is in many respects an example of the lost sense of adulthood, and indeed of the sense of civilisation that helped to create it.

As a result, children are no longer protected from the adult world and we start to see a sexualised education system, one within which what should be, and until recently has been, private and limited to the adult world seeps into primary schools. Similarly, political concerns, of environmentalism and racism, for example, become a burden for children to bear on their small shoulders.

Furthermore, the expectation of identity formation, something that was previously associated with maturity and the world of adults, is found among children at an ever younger age. This is something that is again being encouraged by an education system that has lost its way.

These ‘progressive’ developments are better understood to be pre-modern, helping to move us to a place where the moral content of adulthood has diminished, and with it the very meaning of childhood is degraded.

References

1. Cunningham H. 2006. The Invention of Childhood. London: BBC Books.

2. Ariès P. 1996. Centuries of Childhood. London: Pimlico.

3. Postman N. 1994. The Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Vintage Books.

4. Scott E. 2000. The Legal Construction of Childhood. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia School of Law.

5. Mitterauer M. 1992. A History of Youth. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Is there an environmental generational divide?

Alex Cameron is a member of the SUE editorial board and producer of the Substack. He is a father of three school-aged children.

The notion that there exists a generational divide on the issue of the environment is highly contested. Yet at the same time, whatever the studies show, it becomes just another reason for environmentalists to double down on their regressive vision of the future.

We are told that, ‘there is a clear generational divide in attitudes to climate change’ [1] and that, ‘younger generations tend to feel more strongly about the issue of climate change than their older counterparts’ [2].

Environmental activists of all stripes remain convinced [3], when studies show that the idea of a generational divide is highly questionable. But even those who highlight this disparity nevertheless couch it within a pro-environmentalist/activist framework [4, 5, 6]. Whether there is or isn’t seems to be beside the point. Despite what studies show, environmentalists – from the United Nations to local green groups – always arrive at the same conclusion: more apocalyptic pronouncements are required to legitimise ever more stringent ‘sustainable’ policy demands.

Alternatively, how might we approach this question? In particular, in relation to educational institutions in Scotland? If there is a generational divide, how might we explain it and how should we respond? Should we conclude that young people have a deeper and keener understanding of ‘climate science’? Or do young people simply care more than older generations about society or the future of the planet? Are ‘baby boomers’ so satisfied with their lot that they care not a jot about their children and grandchildren, never mind the planet? Maybe we might consider that Scots under 40 have been schooled in climate catastrophism through the eco capture of schools, the media and cultural institutions throughout their lifetime? Or that the ‘emotional engagement’ (read fear) identified in young people around the issue of the ‘climate emergency’ is being wilfully rebranded as political insight [7, 8, 9].

Whatever the case may be, even if an eco-generational divide was a demonstrable truth, it is not something that should be weaponised and utilised for political capital. Nor would it be a time for adults to ‘leave the room’. Young people expressing fear and anxiety about the coming ‘apocalypse’ is not the result of a healthy political discourse or a sign of democratic political engagement. There is no advantage in such a state of affairs; it can encourage only a debilitating moral and emotional detachment from political, cultural and social life.

In one of too many hagiographic interviews with Greta Thunberg, Jonathan Watts in the Guardian [10] fed us with a narrative that Ms Thunberg protested alone one day and, soon after, was at the forefront of a ‘global movement’. But what is unwittingly revealed in this interview, and the Thunberg phenomena more broadly, is that the 15-year-old (and her enablers) was kicking at an open door. Were it not for the fact that the ideology of environmentalism had been decades in the making among the Western elites, Ms Thunberg’s solo climate protest may have remained just that.

As Watts noted, ‘One after another, veteran campaigners and grizzled scientists have described her as the best news for the climate movement in decades. She has been lauded at the UN, met the French president, Emmanuel Macron, shared a podium with the European commission president Jean-Claude Juncker and has been endorsed by the German chancellor, Angela Merkel’.

Far from a ‘youth-led environmental movement’, what we are witnessing is the ramping up of climate catastrophism by the eco elites, who are, paradoxically, using young people as a source of political authority in an attempt to justify their own no-growth economic agenda [11].

Venerating the likes of Thunberg and the ‘wisdom of youth’ more broadly doesn’t threaten the elites’ grip on power, however slender and politically degenerate it may be, but in the short term at least it can obfuscate and legitimise their eco-austerity programmes and policies.

It is no great leap of faith to believe that most right-thinking people would agree that young people are not political pawns to be used and abused by political ideologues – and shame on those who treat them so.

The problem with the use and abuse of the so-called generational divide is illustrative of a deep-rooted and elite-driven social and political malaise, an existential loss of faith in a transformative political and social project. It is problematic on multiple levels. It speaks to elites that have given up on social, moral and material development; instead, they foster a culture of fear while encouraging antagonism between generations.

The best the new elites have to offer is a future of limitations on material and social development. Their agenda needs a compliant public, and their best hope for that is a generation that has imbibed a culture of a ‘sustainability’.

Furthermore, the promotion of this sustainable, eco-austerity agenda in schools is not about educating students but indoctrinating them, inculcating them into a narrow elitist worldview. It would be a folly to find comfort in the belief that it might not have such a profound effect on the next generation, because we can be certain that it is not going to inspire young people into adulthood with a sense of optimism about the future. Nothing good can come from a cynical and fatalistic outlook.

This is why, however difficult it may prove to be, it is necessary to highlight and problematise the introduction of ideologically motivated ‘educational’ frameworks. We need to find ways to counter their impact, if not dismantle the systems used by doctrinaire activists who are infecting the next generation through our schools. In Scotland, a good place to start would be to challenge the use of third-party organisations who are neither non-partisan nor good-faith actors but have their own explicit, politically driven agendas, and who are taking the place of subject-driven educators. Another would be to challenge the introduction of Learning for Sustainability (LfS) in Scottish schools. LfS is to be embedded in every subject and will encourage the acceptance of a culture of limits [12].

LfS is an elitist political ideology that will infuse every subject at all levels. It is arguably the most far-reaching and coercive systematic change in education in modern history. This alone should have made it a national conversation, but as is becoming increasingly clear, it has been introduced by stealth. The post–Second World War social contract between parents and our educational institutions is being ripped up and recast without parents having a say.

The role of education is to inspire the next generation to be independent thinkers who have been schooled in as wide a variety of opinion and thinking, on any given subject, as is possible. Dogmatism has no place in public life, and certainly not in schools.

References

1. https://www.if.org.uk/2021/09/02/young-people-climate-change-and-political-power-comparing-germany-and-the-uk/

2. https://globalaffairs.org/commentary-and-analysis/blogs/generational-divide-over-climate-change

3. https://www.department22.uk/blog/the-generation-gap-in-climate-change

4. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/who-cares-about-climate-change.pdf

5. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4307001

6. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/05/26/gen-z-millennials-stand-out-for-climate-change-activism-social-media-engagement-with-issue/

7. https://phys.org/news/2023-07-millennials-gen-z-higher-climate.html

8. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-023-00870-x

9. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00278-3/fulltext

10. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/11/greta-thunberg-schoolgirl-climate-change-warrior-some-people-can-let-things-go-i-cant

11. https://www.spiked-online.com/2023/09/05/the-political-exploitation-of-children/

12. https://scottishunionforeducation.substack.com/i/136127115/stretching-the-truth-on-climate

News roundup

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight

https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/23797603.uk-criticised-shameful-culture-war-grr-case-gets-underway/?ref=ebln&nid=1220&u=3113c1b3a77b3e25e409aaa02c22166f&date=190923 David Bol, UK criticised for ‘shameful culture war’ as GRR case gets underway. 19/09/23

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-12510045/BBC-axe-Roisin-Murphy-following-puberty-blockers-trans-comment.html Katie Hind, BBC axes Roisin Murphy songs, interviews and concert highlights from music programme with no explanation – after singer sparked trans row with puberty blocker comments. 12/09/23

https://unherd.com/thepost/why-the-bbc-had-to-memory-hole-roisin-murphy/ Victoria Brown, Why the BBC had to memory-hole Roísín Murphy. The singer has won the argument, so her critics want her silenced. 13/09/23

https://www.theredhandfiles.com/bizarre-and-temporary-world/ Nick Cave, I am 20, high school graduant, in my gap-year and I find it pointless to pursue anything in this bizarre and temporary world that is so much against my values in every way possible. I believe I am speaking for a generation here. I am asking with the biggest admiration, what would you do in my/our situation? 09/23

https://archive.ph/IRfHp Michael Searles, Antidepressant prescriptions for teens hit 1m a year for first time. Experts say this is further evidence of a significant decline in the mental health of young people after the pandemic 12/09/23

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-66709052 Lauren Moss, Trans guidance is needed in schools, parents tell BBC. 14/09/23

https://www.scotpag.com/post/education-blog Carolyn Brown, Is There Evidence of Gender Ideology Indoctrination in Scotland’s Schools? 14/09/23

https://archive.ph/aaVCg Miriam Cates, We can only win from a showdown with Stonewall. Instead of this timidity on trans guidance in schools, the Tories should relish the inevitable legal battle. 14/09/23

Frank Furedi, There is Nothing Inherently Valuable About Diversity: The promotion of diversity breeds intolerance and authoritarianism. 16/09/23

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.