Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No66

Newsletter Themes: Cass Review special, and the need to get transgender ideology out of schools

PLEASE SUPPORT OUR WORK by donating to SUE. Click on the link to donate or subscribe, or ‘buy us a coffee’. All our work is based on donations from supporters.

Because the Cass Review has had such an impact, we thought it worth providing a summary of the key points. In her report, Dr Cass avoids some of the wider cultural and political dimensions of the transgender trend in school-aged children. In so doing, at times she uses ‘transgender’ language, a language that is itself questionable. Her focus is largely medical, or clinical, and with this focus, she is able to highlight some of the appalling practices that breach all sorts of expected standards. In part, it would appear that ideology had (and has) taken over and warped and degraded professional practices – practices that are meant to be there to protect some of the most vulnerable children but that instead have become part of the problem. A key problem would appear to be that in the rush to be ‘progressive’, children and adolescents are treated like adults. More than that, they are treated like adults who understand the solution to their problems (transitioning). In what has become something of a pattern within institutions, here again we find that the adults have left the room, and that a strange new type of morality carries these practitioners (and these unfortunate children) down a potentially devastating path.

As Cass focuses on clinical matters, at times she sees a clinical solution and leaves the door open for the continuation of transgender ideology, for example, in her suggestion that puberty blockers with children could be used in research trials. Based on our understanding that the transgender trend is a dangerous cultural and political (adult) creation that confuses children and adolescents, one that creates a fictitious narrative about being ‘born in the wrong body’, we would oppose this.

Adults can personally identify as they wish. However, as we noted in Newsletter No65, allowing or encouraging children to ‘identify’ before they are mature enough to understand the consequences, will actually undermine their capacity to make free choices in adulthood.

Tragically, what we are witnessing with the transgender trend is a blurring of boundaries that promotes myths and fantasies for often troubled children and adolescents who are struggling with their changing bodies and personal or peer difficulties. For children who feel that they ‘don’t belong’, the idea of being welcomed into a readymade friendship group, a community of LGBT+ and allies, is understandably appealing. From being outsiders or feeling invisible, these children are suddenly celebrated, and celebrated not only online, but tragically, by schools, teachers and practitioners who are, in fact, inadvertently helping to construct the apparent escape route from adolescent anxieties.

New medical advances allow the fantastical notion that you are different from your actual body, but biology is real: no woman will ever become a man, or a man a woman. The result is the destruction of healthy bodies, and rather than growing, maturing and learning to live with their true self, those children who do transition will find themselves in a narcissistic trap, forever preoccupied with their constructed (and medicalised) selves.

Summary: The Cass Review: independent review of gender identity services for children and young people

Rachael Hobbs, SUE’s review analyst, is a teaching assistant and a mother.

Dr Hilary Cass is an honorary consultant paediatrician at Evelina London Children’s Hospital, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. She was closely involved in the development of paediatric palliative care services there.

She was President of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health from 2012 to 2015, Chair of the British Academy of Childhood Disability (2017–2020), and Senior Clinical Advisor for Child Health for Health Education England. Dr Cass has held senior education and management roles in NHS trusts and was Head of the School of Paediatrics in London.

Her clinical practice was as tertiary neurodisability consultant from 1992 to 2018 in three very different specialist centres, and she has published widely in this area.

She was awarded an OBE in 2015 for services to child health.

The Cass Review was a comprehensive examination of NHS treatment for children referred to gender services in the UK. It was commissioned by NHS England to look into escalating referrals to children’s gender identity development services (GIDS), a changing patient profile, and treatment approaches. Despite its damning findings, the report is written in a tone of appeasement, ultimately for the benefit of young patients at the heart of an ongoing saga.

Integral to the assessment was a commissioned research programme, carried out by the University of York, which found a stark lack of evidence of sufficient quality on which to base the treatment routes being provided to patients. And incredibly, requests to access the evidence that would have provided a complete picture of care provided to patients were refused by providers of adult gender services (six out of seven regional clinics)!

Based on the findings of the Review, Cass concludes that the principle of well-established, evidence-based care has not been applied to contemporary GIDS. She reports on the inadequate assessment of a clearly changing patient group, comorbidities (the simultaneous presence of two or more disorders or medical conditions in a patient), treatment pathways, and transition to adult clinics – the last of which is a vulnerable point of transfer for the young (as is perhaps confirmed by the refusal of adult clinics to disclose their treatment data).

Another of Cass’s verdicts is that there was a systematic failure to provide holistic assessment of patients with referrals for gender distress/incongruence, despite such an approach being standard across all other children’s mental health services. The NHS has failed to assess pre-existing or coexisting health issues, thereby, as Cass observes, making an exception of this group; she rightly stresses that ‘They deserve very much better’ (p. 13).

This failure has led to the NHS often following the ‘gender-affirmative’ model in its approach to the care of children referred to GIDS. This is a departure from international guidelines in which this was one treatment path, of several, to be considered with extreme caution – for obvious reasons.

Cass calls for widescale changes, most notably an immediate restriction on the prescription of puberty blockers, with their use limited to research only, as part of clinical trials.

Another recommendation is adherence to a best-practice GIDS model based on the Review’s newly created Clinical Expert Group (CEG). This will establish national standards requiring that services are holistic and include individualised care plans, and that each case is overseen by a nominated clinician to ensure patient safety.

Born in the wrong decade

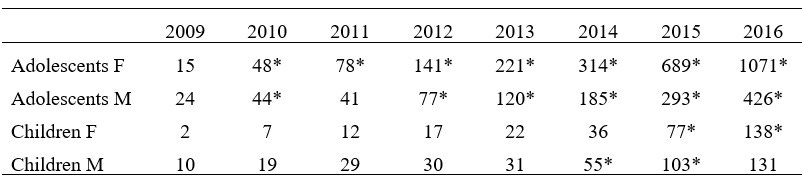

Cass looks at the escalation, over the past 10 years or so, in the numbers of referrals to children’s GIDS – entirely out of proportion for a field previously considered incredibly niche.

Staff working at GIDS, which was established in 1989, once saw fewer than 10 children a year, predominantly prepubertal birth-registered males, and the main focus was therapeutic. GIDS did not attract attention until after 2009; this was a turning point in the demographic of young people accessing services. An escalation in demand in subsequent years has created long waiting lists and a service model unable to cope (p. 25).

Numbers of female (F) and male (M) children and adolescents referred to GIDS in the UK (2009–2016) (adapted from the Final Report of the Cass Review [downloadable here]; p. 72)

* A significant increase of referrals compared with previous years (p < 0.05).

Cass refers to sociocultural factors influencing this new group, saying that ‘the impact of a variety of contemporary societal influences and stressors (including online experience) remains unclear’ (p. 27), and pointing to peer influence as ‘very powerful during adolescence as are different generational perspectives.’ (p. 27).

She notes the vast shift between generations of the legitimacy of ‘gender identity’. Generation Z (born between 1998 and 2009) has seen a sharp increase in referrals, and Cass stresses the importance of having ‘some understanding of their experiences and influences’ (p. 106). This is, for many, an understatement.

Attitudes have changed at such speed that within a 6-month period between early 2020 and late 2020/early 2021, Gen Z adults surveyed in the USA became the first generation in which the majority responded negatively to the statement ‘there are only two genders, male and female’ (p 106).

In terms of service approach, Cass highlights how from 2009, based on a single study (the ‘Dutch protocol’) which suggested that puberty blockers may improve psychological wellbeing for a narrowly defined group of children with gender incongruence, the practice spread swiftly to other countries (p. 13). This was despite the evidence from a 2011 UK trial, in an ‘early intervention study’, the results of which, published in 2015–2016, did not show positive outcomes (p. 25).

Use of the protocol also led to greater rollout of the use of masculinising or feminising hormones at subsequent treatment stages, and critically, this was extended to a wider group of adolescents who ‘would not have met the inclusion criteria for the original Dutch study’ (p. 13).

Cass states that the World Professional Association of Transgender Healthcare (WPATH) has had enormous influence directing international practice, despite the fact that its guidelines have been shown to ‘lack developmental rigour’ (p. 28). Its guidance has moved from a ‘watchful waiting’ approach to one advocating for social transition (p. 158).

The Review found that access to GIDS has been ‘unusual’ in recent years in that staff accepted referrals directly from primary care and from ‘non-healthcare professionals including teachers and youth workers’ (pp. 41 and 217). NHS England has since proposed that all referrals come via secondary care only (p. 41).

Busting a few myths: puberty blockers and social transition

The Report discusses the use of puberty blockers, often claimed by advocacy groups to provide ‘time to think’ for gender-distressed children. Cass clarifies that this is not the case:

given that the vast majority of young people started on puberty blockers proceed from puberty blockers to masculinising/feminising hormones, there is no evidence that puberty blockers buy time to think, and some concern that they may change the trajectory of psychosexual and gender identity development. (p. 32)

These drugs not only suppress puberty but also compromise bone density, and there is little knowledge regarding their impact on psychological wellbeing, cognitive development, cardiometabolic risk, and fertility (p. 32). Cass reports a scant evidence base for the subsequent use of masculinising/feminising hormones. She recommends that these, from the age of 16, should be considered only under exceptional circumstances before the age of 18 (p. 34).

In the UK and globally in recent years, Cass reports that many young people referred to gender clinics have already partially or fully socially ‘transitioned’. Crucially, she highlights that those who had socially transitioned at an earlier age or prior to being seen in clinic were ‘more likely to proceed to a medical pathway’ (p. 31).

She advises that to avoid making premature decisions, clinicians must help families recognise ‘normal developmental variation in gender role behaviour and expression’ (p. 32). If needs be, only partial transition should be considered until a child’s developmental course is clearer, thereby ‘keeping options open’ (p. 32). Cass urges that ‘clinical involvement in the decision-making process should include advising on the risks and benefits of social transition as a planned intervention’ (p. 164).

Cass explicitly states that this is not a role that can be taken by staff without appropriate clinical training (but without naming the likes of school staff and advocacy groups).

Susceptible children and a wider mental health crisis

Since 2009, GIDS has seen an emerging profile of young patients, through a stark increase in teenaged girls, ‘neurodivergent’ groups, those with adverse childhood experiences, and looked-after children (a pattern also seen internationally).

Cass expresses scepticism regarding the ‘greater acceptance’ argument presented by advocacy groups to explain this exponential increase in trans identities, considering the figures to exceed any correlation that might be expected from simply a change in society’s acceptance of a minority (p. 26). She states that, in particular, it ‘does not adequately explain the switch’ in the proportions of patients from mainly males to mainly females (p. 26).

The high proportion of adolescent females presenting to GIDS is, Cass explains, part of a diverse rather than homogenous group of patients – one with wide-ranging co-occurring conditions. Cass urges clinicians to view the escalation in referrals within a broader lens of increasing mental health issues among young people (p. 29).

She discusses the significant increase in adolescents with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a preoccupation with body image. A recent study showed girls to be more at risk, and many are on the autistic spectrum. Owing to the very close correlation between this disorder and that of gender dysphoria (gender distress), Cass urges that this group are able to access evidence-based treatments for BDD (p. 92).

Cass highlights similar mental health presentations within recent profiles of adults referred to GIDS. This is beyond the scope of her remit; however, she mentions that staff have contacted the Review with concerns. Demographics of referrals to adult clinics show ‘the majority of referrals [to be] birth-registered females under the age of 25’ (p. 225).

Cass recommends a new follow-through service for 17- to 25-year-olds within regional clinics, to ensure that the NHS is meeting the needs of these young adults (p. 225).

Regarding neurodivergent patients, Cass explains that they can ‘identify and communicate experiences of stress/distress differently from other neurotypical individuals’ (p. 94). Integration of mind and body can take longer, making them more susceptible into their early twenties or longer, because of greater ‘difficulty in tolerating uncertainty’ (p. 94).

Finally, there is the issue of increasing referrals of children with adverse childhood experiences. Review of the first 124 cases seen by GIDS found that ‘just over a quarter of all referrals had spent some time in care and nearly half of all referrals had experienced living with only one parent’ (p. 94). Furthermore, 42% had experienced the loss of one or both parents, 38% had family physical health problems, 38% had family mental health problems, and 15% had experienced physical abuse (p. 94). Cass stresses that adverse childhood experiences and broader adversity within the family unit are important issues to be aware of when assessing needs (p. 94).

Because referrals also included significant numbers of looked-after children, Cass recommends that social care is embedded within GIDS, as well as expertise in safeguarding (pp. 37 and 211).

Cass explains that gender expression is ‘likely determined by a variable mix of factors such as biological predisposition, early childhood experiences, sexuality and expectations of puberty’, and therefore cautions that mental health difficulties can be a challenge to unpick (p. 27).

Crucially, she stresses that ‘young people are on a developmental trajectory that continues to their mid-20s’ (p. 26). They must be considered in the context of the wider group of young people with complex presentations. A multilayered developmental process is recommended for clinicians responsible for helping these patients (p. 27).

Long-standing gender incongruence, she says, should be an essential prerequisite for medical treatment but is, in itself, still only one aspect of deciding whether a medical pathway is the right option (pp. 35 and 197).

The purpose of children’s gender clinics?

This leads really to an existential crisis for GIDS in agreeing what its services are for, particularly in light of the new patient profile. Cass asks the new CEG to establish consensus on its purpose. Through monumental self-restraint, she addresses ideologues: ‘Although some think the clinical approach should be based on a social justice model, the NHS works in an evidence-based way.’ (p. 20).

Cass also states that ‘Although the focus of the Review is on support from point of entry to the NHS, no individual journey begins at the front door of the NHS, rather in the child’s home, family and school environment. The importance of what happens in school cannot be under-estimated.’ (p. 158; my emphasis in bold). She advises that school guidance be based on principles and evidence from the Review.

She demands ‘Better quality evidence [as] critical if the NHS is to provide reliable, transparent information and advice to support children, young people, their parents and carers in making potentially life-changing decisions.’ (pp. 40 and 216).

What Cass does not do is directly refer to what, for many, is the matter of transgender propaganda directed at the young. However, she does note patients who have told her that a lot of online ‘information’ indicates that any (normal) teenage discomfort with body changes is an indication of ‘being trans’ (p. 120).

It is the job of politics and society to confront what is happening online and more widely, and to form the necessary judgements with which to address how children have found themselves so implicated in this once very adult topic, and anywhere near gender clinics.

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.