Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No51

Newsletter Themes: Burns, learning about the past, and what is history?

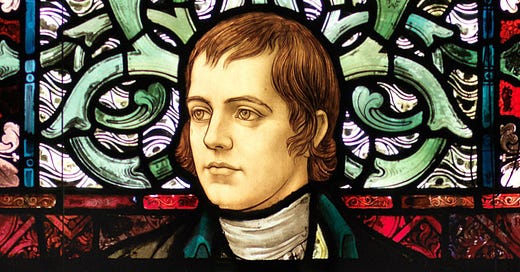

Nichol Memorial Window, Bute Hall, University of Glasgow

It’s a great thing to live in a country which dedicates a winter day and a dinner to the work of its national poet. Ever since my children learned to recite To a Mouse, Burns celebrations have been a great source of optimism for me. It’s comforting to be reminded once a year that Scottish schools are getting to grips with Burns’ poetry and the egalitarian sentiments expressed in poems such as A Man’s a Man for A’ That (1795).

Burns supper is an important tradition, but it has come under attack over the past few years. In 2022, the Scottish Poetry Library commissioned the Trysting Thorns, a group of four women poets, to explore ‘misogyny’ in Burns’ work. Luckily, there are still plenty of teachers and educators who appreciate Burns. Last year, scholars from the Centre for Robert Burns Studies in Glasgow made a strong defence of the poet – and historical thought. ‘Judging dead writers by contemporary morality is “quite crass”,’ Professor Gerry Carruthers told the Herald’s Neil Mackay.

Judging events and individuals from the past based on today’s values is crass. Unfortunately, we live in a world where history and history teaching are at the centre of a wider culture war. This week’s Substack looks at good and bad history. It provides evidence of a creeping ‘presentism’ – the tendency to read and rewrite history and to judge its main characters and authors according to contemporary values.

The SQA’s feedback on last year’s National 5 provides further proof of a problem. The SQA reports that in the course The Atlantic Slave Trade (1770–1807), ‘some candidates were not familiar with the impact of the slave trade on the Caribbean, focusing instead on modern-day moral ethical issues’.

History is always contested, but at is grounded in the idea that through study we can understand how society and individuals have thought and acted. Increasingly, children are taught a limited range of historical subjects and the purpose of history often seems to be to consolidate contemporary prejudices rather than to expand an understanding of our past. In this week’s newsletter, an anonymous parent from Edinburgh reflects on the difference between their own education and that of their child, and Alex Cameron, a parent and designer, reviews E. H. Carr’s What is History?

Penny Lewis, Editor

A lament for history

Some thoughts on the changing nature of history lessons, by an anonymous parent from Edinburgh.

History lessons at my school taught a broad sweep of European culture starting from the fall of Constantinople, precipitating the Renaissance and Reformation, and mostly with a focus on Scottish and British history. The subject was so exciting that I took it at Higher level. The key points in Scotland’s modern evolution were covered: the 1503 marriage of Margaret Tudor and James IV. Then James V; Mary, Queen of Scots; and the Union of the Crowns, pulled off by her son in 1603.

The more gruesome aspects of the seventeenth century were airbrushed with a rush through the Restoration, then the Monmouth Rebellion and the Glorious Revolution until William of Orange ended up in charge. We memorised lots of battles led by the Duke of Marlborough, possibly with too many Northern European battle plans. (I have never needed to recall my youthful knowledge of the Battle of Oudenarde, for example.)

Then back to Scotland for the Darien scheme and the Act of Union in 1707. We then followed the romantic Jacobites on into the eighteenth century. Then there was an overview of the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions; both, we were taught, started in Britain, although perhaps other countries would challenge that now.

We also went from the sabre-rattling Kaiser and assassination of Franz Ferdinand through to the Great War; the subsequent rise of the Third Reich and the Second World War. Always a narrative of the chain of events.

My history teachers were splendidly enthusiastic about the subject: drama and intrigue as exciting as any novel or film. We were expected to cover points across five hundred years, and to memorise dates, battles and monarchs. We also had to analyse key events such as invention of the Gutenberg Press or interwar reparations.

Perhaps my history teachers were the exception. It is commonly held that no one in Scotland learned Scottish history until the establishment of Holyrood devolution. My experience may have been a fortunate aberration, but we answered exam questions set by the SQA of that time.

I assumed my child would enjoy history as much, if not more, than I did. But history seems to have lost its magic as a subject. Nowadays, instead of recounting the big picture and memorising key points along a timeline, my child seems to be taught to personalise everything. Write about the distinctly Scottish emotions of a Scottish soldier in the WWI trenches. Or empathise with the feelings of an imaginary African boy in the hold of a transatlantic slave ship.

The transatlantic slave trade and the First World War are both critical periods, and I’m glad they are taught. But the long view of how one movement or sequence of events led to another seems lacking. When asked what they think of history at school, my child replied, ‘Boring. It’s just essays about: “how do you think this person felt?”’

My child got one shot at school. The learning opportunities you should cover in school – reading, discussing, writing essays, revising, memorising, answering exam questions – don’t get repeated in most people’s lives. If you were turned off by a subject at school, you are unlikely to pick it up later. It is trite, but knowing our history is one of the things unique to humans. Basic knowledge of our past also protects us from the significant volume of garbage one now encounters online. I am sad that my child didn’t catch the history bug at school. It would have stood them in good stead.

Book review

Edward Hallett Carr, What is History? (1961)

Alex Cameron is a member of the SUE editorial board and producer of the Substack. He is a father of three school-aged children. Here he takes a closer look at E. H. Carr’s attempt to describe why history is important and how we can strive for some sense of objectivity and shared understanding in the development of historical thought.

E. H. Carr’s What is History? is arguably more relevant now than when it was first published in 1961.[1] The bulk of Carr’s What is History? is a critique of how historians, from the nineteenth century and through the best part of the twentieth, thought about the function of history (or not, as was sometimes the case) and the role of the historian. As a historical record, if nothing else, it is an important book. The themes raised will be familiar to students today, even though the context has changed utterly. But the book, which began life as a lecture series, is so much more than historical record. Its approach to the subject is such that it enlivens the subject today. At its core, What is History? is a demonstration of the need for a ‘philosophy of history’, how we might understand both its utility and its contested nature. A manifesto of sorts. A foundational document for an optimistic approach to history.

In his lifetime, Carr was a celebrated and formidable thinker who reached beyond the academy. What is History? was republished 11 times in as many years in the sixties and seventies. But in the decades that followed his death, Carr’s reputation has taken something of a beating.[2]

To paraphrase Carr, there is an ocean of facts in history, but some facts are more equal than others. The historian will be judged not by how many or what facts he brings to the fore, but on his expertise in interpreting which facts have historical purchase, which facts shaped our world.

A similarly insightful observation is Carr’s warning against too much emphasis on the ‘individual actor’ in historical enquiry, saying instead, ‘What the historian is called on to investigate is what lies behind the act; and to this the conscious thought or motive of the individual actor may be quite irrelevant.’ (p. 52).

But it is the emphasis that Carr places on knowing who you are reading that is most worthy of attention in this short review. He highlights that the work of historians reveals as much about the present concerns of historians as the time they are writing about. This is an important and key theme in What is History? To know the ‘politics’ or ‘political leanings’ or ‘interests’ of the historian gives the student an insight into the approach and concerns he might take to a particular historical rupture. So, a ‘conservative’ historian might place more emphasis on the dynamics of new market forces and the impact of economic schools of thought, whereas the more ‘leftfield’ historian might highlight the primacy of labour or labour organisations in determining a new set of social relations in a given period.

Carr’s theme was not a justification for consigning one or the other (depending on one’s own political leanings) to the dustbin of history, but to equip the student with the means with which to test the ideas towards a more comprehensive view of events. Knowing the political persuasion of the historian is not relevant so that it can be cast aside, but so we can better understand his perspective and measure the competence of the proposition. We miss the point if we think of history as merely the subjective account of politically partisan historians. We risk history becoming seen as a battleground between ideologues rather than a rich vein of contested accounts of epoch-making forces that shape the present.

And certainly, this insight was never meant as a ‘presentist’ charter. The presentist approach treats history as if we are ‘dooking’ for apples. It is a philistine and ahistorical contempt for the past, by using it as fodder for contemporary ideological concerns. As author Frank Furedi warns, ‘This is a history that gives voice to a powerful cultural trend that condemns the past for failing to live up to the causes and values of the contemporary woke establishment. Through projecting its values into as far back as ancient times, presentism erases the temporal distinction between the present and the past.’[3]

Teaching students about the transatlantic slave trade – as has been done for decades in the UK – is important because it was a significant world event that marked a structural shift in national and international relations, trade, economics and social dynamics. It was an event that changed the course of history – as did its abolition. The importance of this historical moment is diminished when it is weaponised to provide a ‘moral framework’ with which to advance the new ideology of decolonisation.[4]

Similarly, those who attempt to ‘reclaim’ historic figures from a presentist perspective to suit their ideological concerns are ‘flatlining’ history by elevating ‘facts’ over impact. That Joan of Arc is now touted as a ‘trans man’ or ‘non-binary’ is historical deep-mining in the extreme.[5] Whether Joan of Arc was or wasn’t a trans man is surely besides the point when considering the historic conditions that gave rise to her/‘him’. It is seen by these historical gravediggers as ‘fact’, but even if it were true, what does it add to our knowledge of the period? How does this ‘fact’ deepen our historical understanding of Catholic France in the fifteenth century and its victory at Orleans in its Hundred Years’ War with England? How does this ‘fact’ help us understand how France – and indeed England – changed in this period and its aftermath? The answer is, no more than discovering what Joan ate before she was burned at the stake by the English. No, these ‘facts’ are not about understanding the dynamics of history – they are about politics today. They are about advancing the cause of gender ideology rather than advancing our knowledge of human history.

Carr warns against a view of history that, ‘...has no meaning, or a multiplicity of equally valid or invalid meanings, or the meaning which we arbitrarily choose to give to it.’ (p. 109). His approach to history remains important today as a scholarly ‘how to’ guide to approaching historical enquiry or history books, while at the same time it provides a defence against history grifters intent only on serving their ideological needs in the present.

It should be uncontroversial to say that teaching history must be more than the promotion of a new moral framework or a new elitist ideology. To do so robs history of its epoch-defining moments. It subverts history as a critical enquiry. Teaching a pluralistic approach to history is the only antidote to the mining of history to fit contemporary ideological interests.

References

1. https://www.amazon.com/What-History-Edward-Hallet-Carr/dp/039470391X

2. https://www.spiked-online.com/2017/07/28/eh-carrs-sense-of-history/

3.

4. https://historyreclaimed.co.uk/truth-and-decolonising-discourses/

5. https://hyperallergic.com/746319/the-misgendering-of-joan-of-arc/

News roundup

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/only-a-love-of-learning-will-solve-the-truancy-problem-in-schools/ Joanna Williams, Free breakfasts won’t solve the school truancy crisis. 09/01/24

https://archive.is/2024.01.13-013459/https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/fear-of-challenging-our-children-has-broken-scottish-education-j9tk69dhx Carol Craig, Fear of challenging our children has broken Scottish education. The drive to make pupils more confident has morphed into the damaging promotion of US-style self-esteem. 12/01/24

James Esses, Free To Be? The Dangerous Paradox of Gender Ideology. 23/01/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/01/23/islamists-are-wreaking-havoc-in-british-schools/ Frank Furedi, Islamists are wreaking havoc in British schools. Secular education is under concerted attack from hardline Muslim activists. 23/01/24

https://www.scottishdailyexpress.co.uk/news/politics/snp-government-denigrating-scottish-history-31940534 David Walker, The Scottish Government has been blasted by academic Professor Stuart Waiton who hit out at plans to spend £200k of taxpayer cash on creating a museum dedicated to Scotland’s ‘role in empire, colonialism and historic slavery’. 23/01/24

Joseph Burgo, The Revolt Against Authority. We are experiencing a society-wide rebellion not only against parental authority, but against the ultimate authority that is reality. 17/01/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/01/18/the-snps-trans-crusade-will-tear-families-apart/ Alex Cameron, The SNP’s trans crusade will tear families apart. Banning ‘trans conversion therapy’ will criminalise parents who want what’s best for their kids. 18/01/24

Malcolm Clark, Evidence. What Evidence? The LGBTQ+ lobby has got so used to No Debate it has forgotten how to tell the difference between facts and fiction. On Conversion Therapy it now just lies and tries to silence its critics. 16/01/24

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/282240f6-2095-4af8-b516-ff55d8404aa7?shareToken=df559ae98a0afa9a3d2392fd42a7d487 David Sanderson, Morpurgo encourages ‘book clubs for parents’ to help children read. The former children’s laureate has signed a letter that highlights rising child illiteracy. 17/01/24

https://substack.com/home/post/p-140796882?source=queue Joanna Williams, The evil of identity politics. Girls were abused in Rochdale because those in charge feared offending the perpetrators. 18/01/24

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.

Reading through the posts and memories of learning history brought back so many memories. I LOVED history as a kid. It was fascinating. Made me see the world through another lens. I mourn that my child will be denied this experience. Also made me recall a similar experience with my child experiencing Drama. I signed him up for a Summer Musical Theatre program at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. He had never done anything theatre related before. The whole program was a social emotional learning session. Not about the magic and fun of 'pretend', of 'getting outside yourself'. As a result he has turned off to anything to do with performance. The whole premise of the program was to teach kids to 'be kind'. I complained and said 'what makes you assume my kid is not already kind'? It was AWFUL. Makes me weep. All these wonderful experiences being denied to children.