Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No59

Newsletter Themes: parental ‘involvement’ quangos, art school bullies, and education as harm reduction

Copyright Agnes Snow (2024)

Last week’s editorial mentioned the zombie organisation the National Parent Forum of Scotland (NPFS). The NPFS was wheeled out to lend authority to the assertion by TIE (Time for Inclusive Education) that parents ‘overwhelmingly’ supported LGBT-inclusive education. Parents got in touch to express their frustration, to make it clear that the NPFS is the voice of government, not parents. One parent describes the NPFS as a highly ‘secretive’ organisation, and that despite being on a parent council for numerous years, she had never been invited to join.

Apparently, the ‘volunteer-led’ organisation is not a registered charity, but it gets a grant of £133,000 per year from the Scottish government. As it is not really an organisation (there are no individuals or structure of accountability on its website), the funding goes to another quango called Children in Scotland (also funded by Scottish government to the tune of £2–3 million annually in recent years) to provide ‘a broad, balanced and independent voice’. Among its fee-paying members is the campaign group LGBT Youth Scotland, an organisation which promotes social transitioning.

Last weekend, SUE held its annual conference in Glasgow. It was great to see teachers and parents from all over Scotland come together to discuss our education system and how and why it is failing. Issues raised included the decline in reading ability among primary children, the large number of absences in secondary school, and the fact that young children being taught that they can choose their biological sex. Several parents bemoaned the bizarre jargonistic language schools use to describe children’s reading ability, rather than admit that their reading age is below the standard. One parent suggested we launch a reading campaign with the straightforward question, ‘What is my child’s reading age?’, which would allow us to have an honest discussion about falling standards.

It’s very frustrating that the Scottish government is not only failing our children but also organising bogus parents’ campaigns to purportedly speak on behalf of parents. In fact, it’s not frustrating – its chilling. When government gives public money to groups for ‘parental engagement’, it doesn’t want to hear what parents think. It’s actually the opposite: it wants to pay professionals to ‘support’ parents to learn to think and speak as they do.

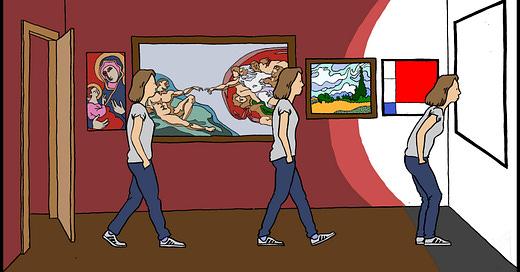

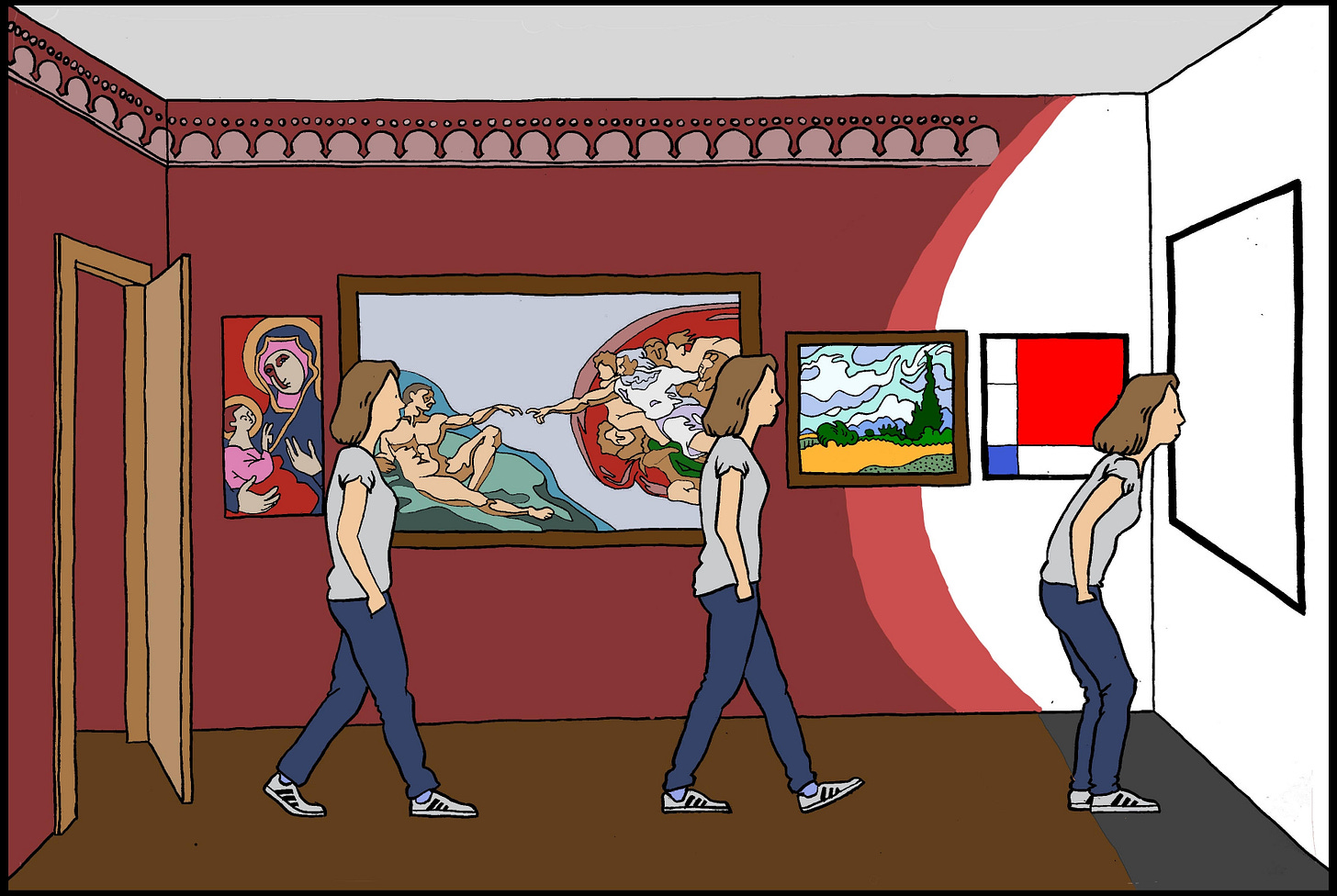

This week’s Substack begins with an article from a young woman who decided to go to art school. SUE has set up a higher education group, and over the next few months, we will carry articles on colleges and universities as well as schools and nurseries. Agnes’s article is funny and beautifully illustrated, but it’s also very sad; university should be a place where young adults get the freedom to think and develop their understanding. The second article is a record of the opening talk given by Stuart Waiton, Chair of SUE, at the Glasgow conference.

Penny Lewis, Editor

Another brick in the wall

Agnes Snow, a school leaver and aspiring artist, tells us about the experience of going to art school. Here is her very personal view of Manchester Metropolitan’s Art Foundation Course.

I was told that taking an Art Foundation Course would help me decide what sort of art I am best at, and that it would help me to know what I wanted to specialise in later. So, I had assumed that it would be a course that taught the practical techniques used in different kinds of art, such things as printmaking and pattern design and what kind of software to use if you want to create digital art. Instead, I have found that the lessons revolve around teaching ‘self-discovery’ and ‘open mindsets’. Not only am I annoyed that this teaching is not what I had expected, but I also don’t believe it really does teach us how to have open mindsets, as it claims.

The lecturers’ method of teaching us how to develop open mindsets involves telling us to do bizarre tasks which it is said are going to cause us to question preconceived assumptions and to teach us how to think expansively. An example of the sort of task we get set would be the Embodiment Workshop. In this workshop, were told to make marks on a piece of paper with charcoal and that we weren’t allowed to hold the charcoal in our hand but should instead strap it to some other part of our body and try to draw or ‘make marks’ that way. In this exercise, the lecturers said that if the marks we were making started to look like anything recognisable, then we were doing the exercise wrongly.

Before doing any tasks, the lecturers generally tell us how good they are at teaching us to question things, and that in doing the tasks they set, we will learn to think in radical new ways. Our lecturers assume that if a student doesn’t want to take part in their workshops, it is because that student is struggling to think freely and have an open mindset, rather than because that student simply believes the workshop to be unhelpful and not what would lead to the creation of good art. I think that these tasks cause the students to be swayed towards the views of the lecturers, because the tasks that the lecturers set reflect their own views. We are only taught one side of the argument and one kind of idea when we are supposedly being taught how to have open mindsets.

I think what would actually help students to develop open mindsets would be to have debates and have lecturers who hold a wider range of views on art. My lecturers’ views on art seem to me to be quite similar to one another, and quite different to the views held by most people in wider society. They seem to uphold ‘transgressiveness’ as the highest virtue in art, and they also have an extremely loose definition of beauty. They have such unusual ideas about beauty that you can find yourself sitting in a lecture in which they are presenting PowerPoint slides displaying plastic bags and broken pegs as examples of what high-standard artwork should look like.

I don’t know quite what the selection process is for lecturers at Manchester Met, but it seems to be one that favours people who hold a particular set of beliefs. I think we should have lecturers with a wider variety of opinions. It is assumed by the lecturers that my views on art are quite common, and yet none of the lecturers themselves share the same beliefs as me. In fact, the lecturers and quite a lot of the students are so keen to be ‘transgressive’ that conventional views like mine are in fact the most controversial sort; they certainly are among the lecturers. To believe that art should be beautiful, and beauty is a certain thing, i.e. not a plastic bag, is to believe that a large part of the students’ and lecturers’ work is no good at all. This is what can make my conventional opinion seem so controversial and awkward.

What are my views on art?

I believe that art students should aspire towards creating beautiful things, and that what is beautiful is what people generally consider to be beautiful. I don’t believe beauty is a social construct but a largely shared innate understanding. I think this shared understanding is what makes beauty valuable, because without it, we cannot appreciate one another’s works and students are left frolicking in their own subjective aims detached from any wider sense of quality. Communication relies on mutual understanding, and this is why our common understanding of beauty is so valuable. I don’t see ‘meaningfulness’ as an excuse for art which is lacking in beauty.

I believe in accumulated knowledge and so I see the history of art as something to be learned from and ‘transgression’ as something that is not a virtue in and of itself; it depends on whether what is being ‘transgressed’ is good or not. And I also think that a large part of art is about developing craftsmanship, and that this has to be done through practice supported by lecturers who teach specific techniques and skills. People say that teaching specific techniques is limiting, but I have come to think that not teaching specific skills is even more limiting; it limits us from learning anything in particular.

If the lecturers in universities across the country had a bigger range of views, and views that better reflect those in wider society, then maybe I would have been able to find the kind of course that I am looking for; at the moment, I am doubtful that it exists. It would not have to be a course that teaches every kind of art. If there was one that just taught painting, it would please me. However, as it is, I can only find courses that boast of teaching students to question what paint is and how it can be applied to the canvas.

A form of art training that I admire is the approach to teaching that was used at the Slade in the 1920s. Before then, British art schools had a specific and limited definition of beauty which made their pupils’ paintings all look rather like one another. And after that time, people have come to have too loose a definition of beauty, which sees it as being anything, such as a plastic bag. The Slade in the 1920s seems to me to have been in the golden era somewhere in between. It was rigorous and harsh enough to demand quality but loose enough to inspire individuality. I don’t think it is a coincidence that an astonishing number of Britain’s most famous artists came out of the Slade at that time. Such artists include the likes of Stanley Spencer, Eric Ravilious, Dora Carrington, John Nash and C. R. W. Nevinson. I get the impression that there was a strong atmosphere of change and innovation in the air at the time, and the students and lecturers seemed inspired.

Next year, I am thinking I might try to find some work experience or go travelling, both of which I think would be more valuable to me in developing artistically at this time than going to university.

Photo: John Rowland

Education as harm reduction

Stuart Waiton, Chair of SUE, gave the opening talk at the SUE conference in Glasgow this month. He talked about how society’s pessimism and obsession with ‘harm’ is demoralising children and undermining the education system.

The Swedish physician and academic Hans Rosling gave a Ted Talk in 2015 called How not to be ignorant about the world. Here, he asked the large audience of largely young professionals three questions about the world.

Question 1. How did deaths per year from natural disasters change in the last century?

a. More than doubled

b. Remained the same

c. Decreased to less than half

Question 2. How long did women, now aged 30 years old, go to school – across the world? (Clue: boys of the same age went to school for 8 years.)

a. 7 years

b. 5 years

c. 3 years

Question 3. In the last 20 years, what happened to extreme poverty?

a. Almost doubled

b. Remained about the same

c. Almost halved

Then came the answers.

Using surveys from Sweden and America and the answers from the audience, Rosling demonstrated that time and again people give the most pessimistic of answers. Few believed that deaths from natural disasters had fallen massively; few believed that girls across the world received almost the same level of education as boys; and the same pessimistic answer was found where few people realised that we have reduced the amount of extreme poverty in just twenty years.

So why was it that the young, professional, well-educated audience that Rosling was talking to got the answers wrong? I do this quiz with my students every year, and I get the same results.

The ‘death’ of progress

This outlook is repeated by so many audiences, across various countries, that it would appear to be an outlook of our time – an outlook, arguably, of the modern elites who strongly influence our culture. In this respect, it can be said to reflect the prejudices of our time.

The usefulness of the Hans Rosling experiment is that it contrasts so starkly with past outlooks towards society, especially those that developed out of the Renaissance and through the Enlightenment, ideals about the ‘perfectibility of man’. Here we find hundreds of years in which we had a sense of human progress and possibilities, an outlook that accompanied and was encouraged by the development of rationality and reason and science and understanding, an outlook that inspired the belief in the importance of a knowledge-based education.

Writing about the ‘Crisis of Man’, Mark Greif notes that from the 1930s there was already a sense of anxiety growing among the cultural elites, an anxiety that cultural critic Lionel Trilling believed was sucking the lifeblood out of the modern American novels. Greif notes that modern cultural products – novels, plays, art – were developed within a culture that was positive about humanity. Earlier, when Shakespeare and Goethe and others depicted human depravity, jealousy, murder and rage, they did so in a context in which a positive attitude towards humanity and progress meant that the works of art were seen as further evidence of the beauty and creativity of man, rather than as a reflection of the depraved nature of mankind.

American legal theorist Bernard E. Harcourt made a stark observation about what happened to society from the 1970s. Where past arguments about law and society were framed in competing moral and political ideals, he notes that from the seventies these frameworks of thought were replaced by ‘harm’ arguments.

Implicit in his writing is a description of two ideals or outlooks: the moral man versus the free liberal individual. By the seventies, moral arguments had begun to lose their appeal, but so too had the ideas of freedom and liberty. In their place, Harcourt notes, we find that from all sides, arguments were now couched in terms of harm and harm prevention. The significance of this observation cannot be overstated, as what he was describing was a transformation in the very understanding of personhood and humanity.

With the diminishing sense of possibilities in the 1970s, the positive ideals associated with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment were undermined, and rather, society (even American society) lost the inspiring sense that Man could ‘Boldly Go Where No Man Had Gone Before’. The liberal commitment to individual freedom of the 1960s had declined, as had enthusiasm for taking risks; what it meant to be human was now to be at risk, notes Harcourt.

The notion of human perfectibility embodied in the ideals associated with human progress was being lost, and in its place, a more defensive survivalist mentality emerged – an outlook that increasingly replaced the belief that people could act on the world to one in which people were understood to be acted on. The doing individual was replaced by the done-to, and one result was that policies, laws – even language – now centred around the idea that we are at risk of harm, and that the best that can be achieved is to prevent harm (rather than do good). Alongside this came the rise of the victim, of the ‘vulnerable group’, and ‘progressive’ ideas about equality and freedom represented through the constructed understanding of ‘protected characteristics’.

Education as harm prevention

Today, in Scotland, a country and culture that were once imbued with a sense of Enlightenment possibilities, we find that education itself is understood through a prism of harm. Schools have become places organised around an ‘ideal’ of harm prevention. We can see this in subjects like Geography. (This is a subject that is being cut from the curriculum in a school in Glasgow as we speak. It is to be replaced by Tourism and Travel.) Geography, used to be about exploring and metaphorically crossing the earth; today, it is increasingly about sustainability and the harms we are doing to the planet.

Similarly, in History, we find that the curriculum is about all the harms that ‘we’ have done in the past. Curriculum favourites include slavery, the KKK, Jim Crow, American civil rights, immigration, and the horrors of war. I’m not saying children shouldn’t know this stuff – we should – but one feels as if these topics are there not to get an understanding about the past, or to look at both negative and positive aspects of history, but to engage with the current political ideas about diversity, women’s inequality, oppression of black people, and the far right. In this way, history becomes all about the present, where our contemporary prejudiced imagination dominates history teaching, and children learn only about the horror and the harms of the past.

Whatever it is, it’s not exactly a balanced perspective, or a review of the Enlightened and progressive ideas developed in the West. And yet it is the ideals of the Enlightenment, of liberty and equality, that helped liberation struggles to emerge and to form individuals like Martin Luther King.

Today, in Scotland, the Enlightenment itself is under attack, and great thinkers like David Hume are recast as bigots. Individuals like Geoff Palmer, the first black professor in Scotland, gives lectures in which he uses a couple of footnotes in Hume’s work to portray him as an influential racist. So dominant is the image of Hume as a racist (at least in the mind of people like Palmer) that when he describes the video of George Floyd’s death, he argues that, ‘When I look at that all I can see is David Hume’!

As a consequence, we don’t need to bother actually reading Hume, or consider his important books and ideas; we can simply erase him from history, and thanks to the ‘educated’ people at Edinburgh University, who renamed the David Hume Tower ‘40 George Square’, we’re on our way to doing that.

As we pull down statues and cover them with plaques explaining how racist they all were, we find activists arguing that these inanimate objects literally harm them. History equals Harm (literally).

It goes much further than just a few subjects changing their material, and we find that all subjects in Scotland are being encouraged to incorporate ‘anti-racism’. Even in Maths, experts say, our imagination turns to deeply embedded ideas of whiteness!

The Harm Principle now envelops schools and education. It is not just about the teaching and the content of subjects; there is a new morality – a new ethos – a seemingly ‘caring’ ethos that helps to create a new culture, a new way of speaking, new ‘correct’ ways to behave and to feel.

In the General Teaching Council for Scotland’s The Standard for Headship document, which spells out what you need to be a headteacher, we find almost nothing about education and an awful lot about ‘social justice’ and the need to be ‘sustainable’, ‘inclusive’, ‘diverse’ and ‘safe’, so that children, especially those with ‘protected characteristics’, can grow without experiencing ‘trauma’.

The harm prevention approach is evident in the constant talk of transgender rights in schools – where any form of questioning of a child’s identity is couched in terms of suicide and suicide prevention. Similarly, LGBT education is promoted as being all about bullying, and anyone who questions this agenda is recast as an uncaring bigot. In this new world, to question the idea of trans identities for very young children means you are leading a child to suicide, and to question LGBT-inclusive education is tantamount to giving the thumbs up to the bullying of gay kids!

The same harm reduction outlook is emerging in the discussion about misogyny in schools and the need to teach boys how not to be misogynists. The First Minister appears keen to promote anti-misogyny education and, in the process, to increase further the image of boys and men as part of a ‘rape culture’.

We find that children are being increasingly diagnosed with mental health conditions, and that children themselves are being educated to think about themselves through these mental health categories. But it is not just some kids who are given labels and a diagnosis – the very essence, the heart of education in Scotland, is now about ‘wellbeing’ and the need to protect what are understood to be emotionally fragile children.

Scottish education is, in essence, a protection racket. From the subjects taught, the social justice politics surrounding it, through to the new ‘caring’ ethos connected to bullying, suicide and everyone’s mental wellbeing – children are being educated through a prism a harm. Even what it means to be educated is changing, seen for example through the idea of ‘educating yourself’, a term used by awareness-raising professionals that basically means, ‘Be aware of your vulnerability and the vulnerability of others – be aware of harm’.

Education and progress

Thankfully, what I am describing is only part of what happens in schools, but it is part of a new ethos within education. As Hans Rosling’s examples show, it is not Scotland-specific and there is a certain cynicism in our culture about the modern world and past generations. Many of the problems we face today are dumped on older generations, who are increasingly portrayed in a one-sidedly negative way; the old, in a sense, embody the past, and as we know, the past is little more than a litany of harm. Scottish government documents casually portray the need to ‘unlearn the prejudice taught to us by the older generations’. Or we find that children are educated to understand that the planet’s problems are because of generations of greed. We find a sense of history that is little more than a dark cloud from which young people must escape. Or, as ‘progressive’ thinkers like Geoff Palmer put it, as long as historians and educators say nothing about people like David Hume, and our slave-riddled past, people are going to continue to believe that ‘negroes are inferior’.

This debased view of Scottish people should act as a warning cry for all of us. Because this cloud around the modern world and the past has serious implications, not simply in its miserabilist nature, and the one-sidedly negative dimension of it, but because education is history. I mean that education is when we pass on the knowledge of the past to the next generation – when we help them up onto the shoulders of giants so that they can see into and create a better future.

Understanding education as history means taking children seriously and believing in their capacity to learn difficult, sometimes very difficult, subjects. We are handing over to them our collective knowledge. School subjects are key because they are how humanity has attempted to break down frameworks of knowledge that have developed over hundreds of years – a framework that has helped us to develop an ongoing comprehensive understanding of the world.

If the educational authorities think that human history and human knowledge developed across time is little more than a history of bigotry and harm – a dark cloud from which young people should escape – they cannot educate our children.

If we lose a sense of the enlightening potential of knowledge, knowledge itself diminishes, and the meaning of education is confused and teachers lose their status. Rather than educate children (and indeed university students), teachers are encouraged to flatter them – or at least to not ‘stress them out’. So at Glasgow University, students are panicking confronted with in-person exams, invigilated exams, rather than their poor online equivalent. This is less a poor reflection on the students themselves but of the system that has instilled a sense of vulnerability, a sentiment that turns exams into yet another form of harm.

So, what can we do?

We can point to what is happening in schools and at the collapsing standards that accompany this harm prevention education, and we can highlight how this highly limited and limiting ethos in schools underpins the ‘progressive’ approach to education and undermines children themselves.

We also need to highlight the positives and to recognise that there is a growing movement across Europe to challenge this ultimately philistine approach to education. There are many great minds and great thinkers who are pushing back and demanding that standards are raised, and that a serious and enlightened knowledge-based education is developed.

Even within SUE, within the space of a year, we have found individuals across the UK who have inspired us with their research and writing. And we find a growing number of individuals within education who are standing up to the trolls and to employers and institutions who attempt to censor their views because they are deemed ‘harmful’.

And we are finding a growing number of parents who, unlike our modern elites, have a far more balanced understanding of the world, of its problems, but also of possibilities. Ordinary people in Scotland are far less negative about their past and their history, and similarly, they have a far more balanced understanding of what children are and what they are of capable of. They also have a more reasonable, rational and common-sense understanding of what schools should be about.

The future can often look bleak, but collectively, those teachers who still have a passion for their subject and those parents who desperately want a good, knowledge- and subject-based education for their children, have the potential for creating a collective alliance to ensure that this, and future generations, have a truly enlightened education.

News round-up

A selection of the main stories with relevance to Scottish education in the press in recent weeks, by Simon Knight.

https://archive.is/Vyy2h Daniel Sanderson, Give playgrounds girl-only slots to counter ‘toxic’ influences like Andrew Tate, SNP says. Scottish Government publishes raft of plans to combat rising gender-based violence in its schools. 04/03/24

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-68475150?fbclid=IwAR1dHp9RyfAFHV4M8wP3HuolmovsmMrgkHDq_PweiAkn9pOYBH92zcAEdWY_aem_AZUW8WNzwQ4yqJedKPVP6WHERn2UUjBNWlt6il52BtF2yzlkmzXZMrvZQGVkaGi-Fcs Rebecca Woods, Toxic culture of fear in swimming systemic - review 05/03/24

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/03/06/the-church-of-critical-race-theory/?utm_source=Today+on+spiked&utm_campaign=466adaf18e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_03_06_04_44&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-466adaf18e-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D Alka Sehgal Cuthbert, The church of critical race theory. The Church of England is prostrating itself before a divisive racial identity politics. 06/03/24

Academy of Ideas, The battle for women...

To celebrate International Women's Day, we dig into the Battle archives for some of our favourite female freedom fighters. 08/03/24

WorldWrite, Sylvia Pankhurst: Everything is Possible.

https://www.spiked-online.com/2024/03/08/trans-the-medical-scandal-of-the-century/?utm_source=Today+on+spiked&utm_campaign=2b6eae937d-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2024_03_08_07_09&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-2b6eae937d-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D#google_vignette Lauren Smith, Trans: the medical scandal of the century? The WPATH Files have exposed the terrible harms of ‘gender-affirming care’. 08/03/24

Frank Furedi, Policing Intimacy Affirmative Consent Campaign Leads to The De-Moralisation of Intimacy 09/03/24

https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/politics/snp-msp-tells-parents-teacher-32307137 Paul Hutcheson, SNP MSP tells parents teacher numbers are a 'luxury we can no longer afford’. EXCLUSIVE: A leaked email has revealed John Mason defending the prospect of a fall in teacher numbers on Scotland's largest local authority. 10/03/24

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c3gmvyxexlzo No credit, Arts body to review £85k funding for 'hardcore' sex project. no date.

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.

Statement from Creative Scotland on Rein

Published: 14 Mar 2024

Following a review of the application, assessment, and contractual agreement regarding the project Rein, Creative Scotland has made the decision to withdraw support for this project and will be seeking recovery of funding paid in respect of this award to date.

Going by Stuart Waitons opening speech, I really hope to make the next conference.