Scottish Union for Education – Newsletter No48

Newsletter Themes: are Scottish schools really racist? Plus a review of a new book by a critic of decolonisation

Happy new year! To start 2024, we want to talk about racism. I agree with the Scottish government that it is ‘unacceptable for people to experience disadvantages due to structural racism or discrimination on the grounds of colour, nationality, ethnicity or national origin’ (Anti-Racism in Education Programme), but are schools the right place to address structural racism and discrimination?

Last year we received reports of classes in which white pupils were taught to recognise and acknowledge their ‘privilege’ and trainee teachers were taught ‘white guilt’ as official policy rather than as a contested theoretical concept. We also received reports that an Edinburgh school had set up a ‘non-whites’ section of its parent council. New so-called ‘anti-racism’ policies and activities are promoting a racialised worldview in which all white individuals carry responsibility for poorer social, economic and representational outcomes of minority ethnic individuals and groups.

These divisive developments are the outcome of the Scottish government’s Anti-Racism in Education Programme, which was introduced in 2020 during the Covid pandemic. The driving force behind the policy was ‘the significant amount of correspondence received by the Deputy First Minister as part of the Black Lives Matter movement and one of the recommendations made by the COVID-19 Ethnicity Expert Group, seeking to include the teaching of Black history in the curriculum’.

This racialised way of understanding the world is not shared by many parents, but this mismatch between educational policy and the wider attitudes of the population has not been openly discussed in parent councils or by local authorities. Parents expect children to be taught that we are all equal and should be treated as such, because it’s a foundational established idea in modern society; they don’t expect their children to be taught that they are personally responsible for any of injustice experienced by people of colour across the globe.

The government’s stated ambition is to create an education system and teaching staff that are ‘race literate as opposed to race evasive’, which translates as: it is no longer enough for schools to ensure that all children are treated in the same way, as equals; instead, teachers need to make an issue of our differences, and they need to politicise the issue of race to ensure that white children understand their role in a systemic process of racial discrimination.

According to this official ideology, parents and teachers who aspire to a ‘colour-blind education system’ are now dismissed as ignorant, unaware or racist. Schools are being encouraged to politicise race, and quite young children being expected to grasp a wide range of issues related to racism and social injustice. Teachers are being trained to see their role as ‘raising the awareness’ of our children.

SUE is keen to challenge the government’s Anti-Racism in Education Programme both because it is divisive and because the ideology that underpins it is flawed. This week, Stuart Waiton, Chairperson of SUE, kicks off the debate with a review of latest government report on racism in schools and an analysis of the data on racism in society and universities. He finds little evidence of a problem in higher education and suggests that policy-makers are pressing forward with ‘anti-racist’ policies regardless of the evidence. Meanwhile, Rachael Hobbs has been looking at some of the literature that is critical of decolonisation. She reviews Doug Stokes’ book Against Decolonisation (Polity, 2023).

SUE will be looking at this issue of ‘anti-racist’ education over the next few months and welcomes articles and letter from anyone with experiences or thoughts on racism, teaching, and education.

Penny Lewis, Editor

Follow SUE on X (FKA Twitter)

The moral panic about racist schools

Stuart Waiton is Chairperson of SUE.

There is a lot of talk about racism today. Part of this talk comes in the form of new principles and practices being developed in Scottish schools and in higher education. We are being asked to ‘decolonise’ the curriculum in universities, and to help to make Scotland the ‘best place to grow up’, where children can learn in an ‘inclusive environment which is actively anti-racist’.

The Scottish government’s Anti-racism in Scotland: progress review 2023 states that ‘anti-racism’ is now being embedded in ‘early learning and childcare settings, schools, further and higher education institutes and community learning settings’.

Anti-racism can be thought of as being political. As such, it raises questions about whether it should be being introduced into schools and even nurseries. However, it is also part of a wider framework, a new moral framework associated with good ‘values’ and good behaviour. Being ‘anti-racist’, we are informed in the review document, is about ‘safeguarding children’s rights’ and ensuring ‘child-centred learning’.

All staff, the report explains, ‘are expected to be proactive in promoting positive relationships and behaviour in the classroom, playground and the wider school community – a condition of teachers’ ongoing registration with the General Teaching Council (GTC) for Scotland’. So to be employed as a teacher, you must be anti-racist; moreover, you must be actively anti-racist. You must, essentially, adopt the ‘social justice’ perspective promoted by the GTC, and schools and headteachers must build ‘racial literacy at all levels within the workforce’.

In my past days as an active anti-racist, I spent much time on street corners and public meetings and demonstrations (or counter-demonstrations when the British National Party were more active) talking to adults about racism. It would never have occurred to me back then to challenge racism by going into nurseries and schools. Nor could I have ever imagined that anti-racism would become embedded in the curriculum or that it would become a new type of etiquette, or a values system that would determine whether you can actually become a teacher or get a promotion.

I thought it might be useful to kickstart the discussion on anti-racist education with a question: Is the problem of racism so severe that we need to enforce anti-racist lessons on teachers and children? Sometimes we are told that the Scots are more tolerant than the English; at other times, that racism is on the rise across the UK. Much of the data on this subject applies to the UK, and as such it provides an important counterbalance to the panic stories about racism in Scotland and England.

In the past we’ve looked before at various claims about racism in Scotland, for example the idea that due to Britain’s colonial past, ‘Black students are still made to feel themselves to be inferior and less intelligent, and are often regarded as more criminal in the eyes of peers and those in authority’. Is this true?

Looking at the results of Ipsos research in 2020, we find that 89% of those asked (across the UK) said they would be ‘happy for their child to marry someone from another ethnic group’. Additionally, 93% ‘disagree with the statement that, “to be truly British you have to be White”’.

The British Social Attitudes Survey has noted that there has been a consistent decline in racist attitudes over time in the UK, with one academic paper noting that there was ‘strong evidence’ for this, with ‘evidence of an overall decline in prejudice and of a sharp decline in prejudices among generations who have grown up since mass black and Asian immigration began in the 1950s’.

Comparisons with other European countries (despite fears about Brexit) have also found that the UK is one of the least racist countries, with racist attitudes being ‘relatively low’, and religious prejudices being lower in the UK than in countries including Spain, Italy, Finland and Germany. Co-author Professor Mariah Evans notes in the report that pundits were wrong to associate the UK’s vote to leave the EU with prejudice.

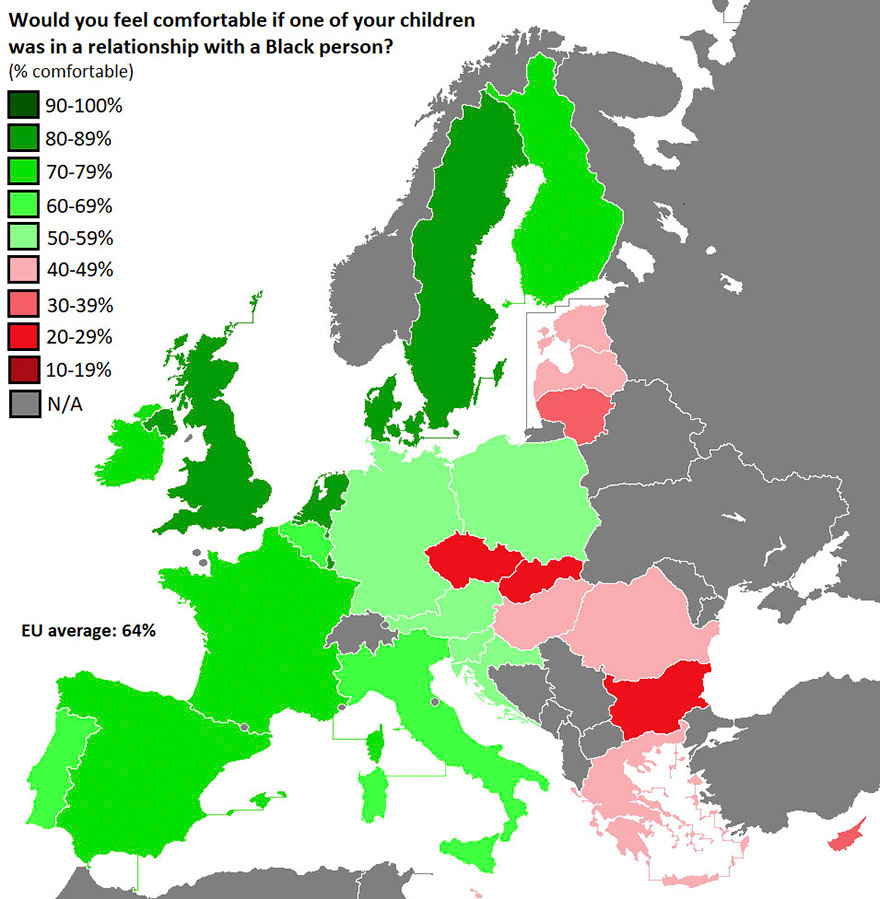

An EU study initiated in 2015, when the UK was still in the EU, surveyed European citizens about whether they would be comfortable if one of their children was in a relationship with a black person. The UK, alongside Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, were the most tolerant nations, with over 90% of respondents saying that they would be comfortable with this.

By 2019, an EU report, Being Black in the EU, presented findings showing that the UK was the least racist country of the 12 European countries it studied.

Similarly, the Runnymede Trust found that there has been a significant shift in attitudes in the space of a generation regarding who people thought were ‘truly British’, how many people supported ‘equal opportunities’, and the numbers of people who thought that immigration was ‘good for the economy and cultural life’.

Already, by 2011, the UK census was reporting a major increase in interracial relationships, with a doubling of the numbers since 2011. And by 2020, a report by the Creative Diversity Network found that representation of non-white individuals within the media stood at a ‘remarkable’ 23 percent, well above the 14 percent of the British population who are of minority ethnic origin.

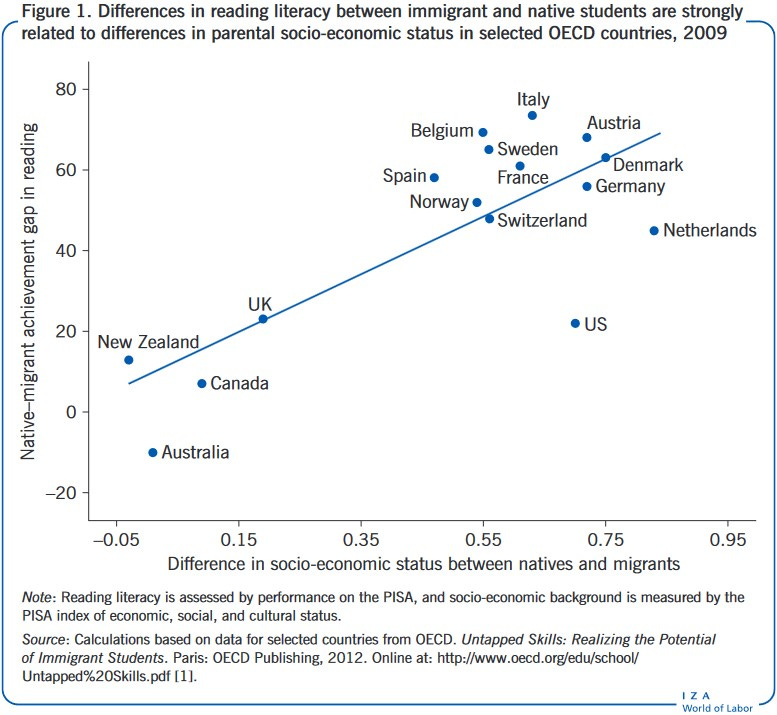

Furthermore, in the UK, the difference in socio-economic status between ‘natives and immigrants’, is lower that every other European country, and the UK (unlike other European countries) has one of the lowest educational gaps between ‘natives and immigrants’; even first-generation migrant students do comparatively well (although this is helped, in part, by many of these migrants already speaking English as a second language).

When it comes to educational achievements, there are, at times, generational differences, with second and third generations of non-‘native’ members of the UK population doing better than their parents and grandparents, in part due to intergenerational wealth being built up. The race-education issue is also complicated by the fact that different groups of people achieve at different rates. For example, British-Nigerian pupils achieved substantially better results at school than the overall mean rate, and much higher than the results of white British pupils.

This is not to say that racism does not exist, nor that it is not a problem; however, worries about the extent to which it is a problem appear to be misplaced, and the extent to which we appear to think that racism is rife across the UK appears to be excessive. Where we find around one in 10 people have racist attitudes, much of this is from those in the most elderly sections of society, many of whom are retired and have little or no influence on institutions, especially perhaps within education. Staff in educational settings, such as universities for example, are generally even more liberal-minded than the general population, which would suggest that racist attitudes would be extremely rare within these institutions.

The trend in all serious pieces of research is to show that racism across the UK is low, often lower than many and sometimes any other European country, and that it is getting ever lower.

However, perceptions of racism remain relatively high. The Ipsos research mentioned above, for example, found that despite the falling levels of racism, concerns about levels of racism are increasing, and there does appear to be a far higher sense of the problem of racism than the amount of actual racism in society. Why is this?

One of the reasons is that there is a plethora of research, some carried out by groups with an agenda, as well as others, and carried out using deeply flawed methods, that promotes the idea that racism is a significant and even a growing problem.

One such piece of research looking into racism in universities, carried out by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), led its chief executive to conclude that universities were ‘not only out of touch with the extent that [racism] is occurring on their campuses, some are also completely oblivious to the issue’. However, when we dissect this report, we arguably find that there is both an inbuilt bias and serious methodological flaws in the research which led to the construction of the idea of racist universities.

Having conducted a serious study of the EHRC’s report, Tackling Racial Harassment: Universities Challenged, Wanjiru Njoya and Doug Stokes explain that due to small sample sizes, a lack of sensitive analysis, and a one-sided approach, the EHRC paint a picture that is not justified. They conclude that ‘far from showing that British universities are riddled with racism, the data clearly show that they are remarkably inclusive, non-discriminatory institutions’.

When looking at the claim of racial harassment of students, they demonstrate that if done correctly, we discover that ‘In a three-and-a-half-year period, where 9,200,000 students passed through the U.K.’s higher education institutions, 0.006 percent of students reported incidents of racial harassment to their universities’. The EHRC attempts to explain this extremely small figure by suggesting that it is an example of under-reporting possibly due to the lack of confidence that minority ethnic students have in the university system. But this is not backed up by their own research, which shows a relatively high confidence in universities tackling issues of racial harassment.

This is just one of many examples of questionable research that promotes the idea that the UK (including Scotland) are racist places in which to live and to study. I saw something similar in Dundee, where based on seriously and rather embarrassingly poor research, the principal of the university, Iain Gillespie, argued that the racism in his own institution was ‘shocking’.

Rather than there being a serious and growing problem of racism in Scottish schools and universities, the very opposite appears to be the case. To find an explanation for the state-enforced anti-racist education in our schools, one would suggest we need to look far less at the supposedly racist attitudes of children and their parents and to look instead far more carefully at the presumptions and the prejudices of the people who run our educational institutions. As Wanjiru Njoya and Doug Stokes argue, the more we look at the claims of racism in education, the more we discover that it is our ‘progressive’ elites who are responsible for creating a dangerous moral panic within our schools and universities.

Book review

Doug Stokes, Against Decolonisation: Campus Culture Wars and the Decline of the West (Polity, 2023)

Reviewed by Rachael Hobbs. Rachael is a teaching assistant and mother.

Doug Stokes has acted as Director of the Strategy and Security Institute at the University of Exeter, is a Senior Adviser to the Legatum Institute, and a member of the Advisory Council of the Free Speech Union. You can follow him online at @profdws or www.dougstokes.net. His new book, Against Decolonisation (Polity, 2023), is an important contribution to the discussion on the rise of identity politics and its sponsorship by corporates and some of the most affluent elements of society.

‘Decolonisation’, Stokes tells us, is not to be confused with the historical end of empire; rather, modern ‘decolonisation’ is belief in ‘the process of freeing an institution or sphere of activity, from cultural or social effects of colonisation’.[1]

‘Decolonisation’ is based on the belief that post-colonial structures maintain the interests of ‘white hegemony’. It deems that racism is, to the present day, structured into every aspect of society, and by extension, what we think, feel, and impart as knowledge. It extends far beyond tokenistic diversity or attentiveness to prejudice and demands overhaul of teaching to approved ‘anti-racism’ pedagogy, instructing students about ‘white’ power. It is also calls for removal of the western world order.

One of Stokes’ key arguments is that decolonisation is a product of the very thing it rebukes: western liberalism. He argues that rather than being an altruistic grassroots movement, it is propelled by a cultural elite, empowered by declining national decision-making under globalisation, to the detriment of ordinary people. Stokes argues that the decolonisers’ aim to question of the West’s sense of itself, deconstruct its narratives, and overthrow its institutional order is an aspiration that is ‘underpinned by a more confident and assured Western hegemony’, which is now unravelling and coming under great strain.

So, how and why has a marginal political mission become prominent in an era of settled legal and cultural equality? Why are corporations posturing as revolutionaries against the ‘system’ with their unconvincing self-flagellation?

Stokes has undertaken detailed analysis of the research and data that appear to underpin the process of decolonisation on education. Decolonisation’s rollout started in universities, strangely from a place where there was an evidence base that contradicted the decolonisation thesis. The Equality and Human Rights Commission carried out several surveys about racism in higher education. The big data reveal from a 2018–19 survey was that just 92 of 1009 white and ethnic minority students surveyed had experienced racial harassment (8%).[2]

A second report, from 2015–19, aimed at those with direct experience of racial harassment or those witnessing it, found that only 2.3% of staff and 3.6% of students reported racial harassment; 4 in 10 universities reported no complaints from staff, and 3 in 10 reported no complaints at all.[3] These results allowed claims of endemic racism across campus culture.

Advance HE, the key governance body for universities, went swiftly on to produce the Race Equality Charter (REC), with a founding principle that ‘racial inequality is a significant issue within higher education’.[4] Looking at the data, this is simply not true.

Universities have nevertheless had to self-assess, via REC, to receive accreditation conditional on promotion of diversity and of black and minority ethnic (BAME) staff to senior roles, ‘decolonising’ of teaching, and ‘training’ in contested ideas of structural racism and ‘whiteness’.[5]

Universities UK, the collective voice of university management, also directed universities to adopt ‘anti-racism’. This involved concepts such as ‘white privilege’ and ‘unconscious bias’ applied to whole areas of study denigrated as ‘western-centric’, and a deliberate move away from works of renowned white scholars, whether they were foundational contributors to a topic or not.

Decolonisation’s programme has no mandate. The Higher Education Policy Institute found that only 23% of the public supports it. This was deemed by head of University and College Union as symptomatic of a country of bigots: ‘The level of hostility towards decolonisation activity shows just how far we have to go to tackle systematic racism’.[6]

Additional justification for the agenda is that universities are under-representative. Data again proves the contrary. Between 2003–04 and 2019–20, the proportion of staff who were ‘UK white’ decreased (from 83.1% to 70%). During the same period, ‘UK BAME’ staff increased from 4.8% to 8.5%, and ‘non-UK BAME’ staff from 3.8 to 7%. The non-white UK population is 18%, thus the statistics show over-representation of BAME staff.[7] For students, the biggest increase in entry rates since 2006–18 is among black students, at 19.6% (21.6%–41.2%) and the smallest is white pupils, at 7.7% (21.8%–29.5%).[8]

Stokes argues that Advance HE overlooks its own data to sell its REC. In comparison with positive BAME representation, the group consistently under-represented is white working-class young adults. Universities have no inclusion plans to address this issue, despite class being the lead indicator of life success.[9]

In a 2021 report, based on data for free school meal (FSM) eligibility, a primary index of deprivation, the proportion of FSM-eligible white pupils starting higher education by the age of 19, in 2018–19, was 16%, the lowest of any ethnic category aside from traveller groups. FSM-eligible Chinese pupils’ entry rate was 72.8%; black African pupils’, 59%; and black Caribbean pupils’, 31.8%.[10]

Stokes pulls apart the subjective nightmare of decolonisation. He suggests, instead, that it has emerged from an altogether different prevailing power structure: quasi-national institutions and a cultural elite pushing a narcissistic culture.

He draws on theory which argues that accelerated globalisation since the 1970s created networks and a hierarchically dominant ‘professional managerial class’ that surpass national government. Settled working-class communities have been superimposed by globalisation of labour and capital, with manufacturing replaced by an international services economy; and these transitions have been managed by the managerial class. This cultural order emphasises individualism and self-discovery over community.[11]

Globalisation enabled geographical mobility for this group, leading to, ‘An emergent new class between the “anywheres” who have achieved “identities derived from their careers and education” and the “somewheres” who get their identity from a sense of place and people around them and feel a sense of loss due to the fragmentation imposed by globalisation and rapid social change’ (see also David Goodhart’s The Road to Somewhere, 2017).[12]

This order encourages pursuit of identity, superseding any struggle for economic freedom for those who cannot access a top tier of ‘analytical-conceptual’ careers (reserved for elite graduates). Effectively, ‘Identity/diversity are a precondition for a global elite who identify other members capable of living in a cultureless and placeless world defined by indifference to actual communities.’[13] The emergent global order defends authoritarian identity movements and ‘polices working class political agency’ under the guise of countering ‘vulgar populism’ when there is dissent.[14]

This leads us perhaps to a competing structural theory of power which identifies not white hegemony but a global authoritarian order based really on woke capitalism. Stokes outlines that new ‘quasi-autonomous’ governance networks are removed from domestic politics and consent and positioned, instead, ‘legalistically’ within ‘rights’ frameworks which benefit an elitist ideology.[15]

Stokes’ argument is that decolonisation, as part of this wider framework, separates people, particularly the young, from their sense of country, society, and collective cultural belonging.

References

1. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/decolonization

2. Stokes D. 2023. Against Decolonisation: Campus Culture Wars and the Decline of the West. Cambridge:

Polity; p. 37.

3. (Stokes, 2023, p. 37)

4. (Stokes, 2023, p. 40)

5. (Stokes, 2023, p. 40)

6. (Stokes, 2023, p. 50)

7. (Stokes, 2023, p. 60)

8. (Stokes, 2023, p. 60)

9. (Stokes, 2023, pp. 76–77)

10. (Stokes, 2023, pp. 76–77)

11. (Stokes, 2023, p. 127)

12. (Stokes, 2023, p. 128)

13. (Stokes, 2023, p. 129)

14. (Stokes, 2023, p. 128)

15. (Stokes, 2023, p. 129)

Thanks for reading the SUE Newsletter.

Please visit our Substack

Please join the union and get in touch with our organisers.

Email us at info@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Contact SUEs Parents and Supporters Group at PSG@scottishunionforeducation.co.uk

Please pass this newsletter on to your friends, family and workmates.